This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

New York comes alive in the summer. All that pent-up kinetic energy from the long winter collects, then the fire hydrants crack open and the colliding pressures coursing through each block and borough burst onto every sidewalk. It’s open season for the good and the ugly, and for the past three years, summer in the city — the whole city — has sounded like drill music. Just over a decade ago, a sprawling ecosystem of mainly teenagers in Chicago’s South Side who grew up with trap’s mixture of no-holds-barred realism and aspirational escapism found a way to distill the conflicting feelings of their neighborhood into a new rap subgenre. Drill — pushed into the mainstream by artists like Chief Keef and translated as far and wide as London and, later, Brooklyn and the Bronx — created a potent, grisly language for a community to talk to itself about what it meant to call a metropolitan war zone home. It got its name from the kill-or-be-killed mentality (the word literally means “to shoot”), a code wherein black-and-white ideas about morality are sacrificed in the name of survival. There is an unflinching sense of desperation reflected in drill. Like all hip-hop, it is a culture born of suffering and a desire to alchemize the pain, and so, like many rap scenes before it, the music and those making it have been misread as causing harm instead of working through harm done.

In New York, on any given day this summer, you might hear a high schooler cut through a bustling McDonald’s on Atlantic Avenue to announce to her friends that South Bronx star B-Lovee just posted something hilarious on Instagram and then immediately clock his friends Dougie B and Kay Flock wailing through a car’s speakers on their hit with Cardi B, “Shake It.” But as popular as drill has become since Canarsie’s Pop Smoke welcomed the city to the party in the spring of 2019, it has also made countless enemies. It took less than a year for the NYPD to direct its so-called hip-hop unit to surveil drill on social media. They combed through lyrics and music videos for clues of any crime, leading to artists being pulled from the lineups at major rap festivals in the city, shows being shut down hours before opening, and, increasingly, mass indictments targeting gang affiliates, an unavoidable birthright for far too many of the city’s children.

Earlier this year, Mayor Eric Adams, incensed by the murders of two local drill hopefuls, met with several members of the scene for a summit on what the city can do about drill and the role he suggests it has played in an uptick in bloodshed throughout his constituency. If there is as much violence engulfing New Yorkers as he (and other mayors before him) says there is, then the art produced by the city’s lifers can only report the truth: Living here is to be at constant odds with loving it here. Here, you’ll hear from several members of this new generation coming out of the five boroughs, some of whom are currently incarcerated, and the stories of pride and pain they’ve been fighting for their lives to tell for as long as the city passes the mic to them. No single person can speak for New York, but is it possible a sound can? —Dee Lockett

New York drill, as told by …

.

19 artists who define the scene.

The tragedy of Jayquan McKenley.

The sound itself.

The essential tracks.

Lawyers and lawmakers.

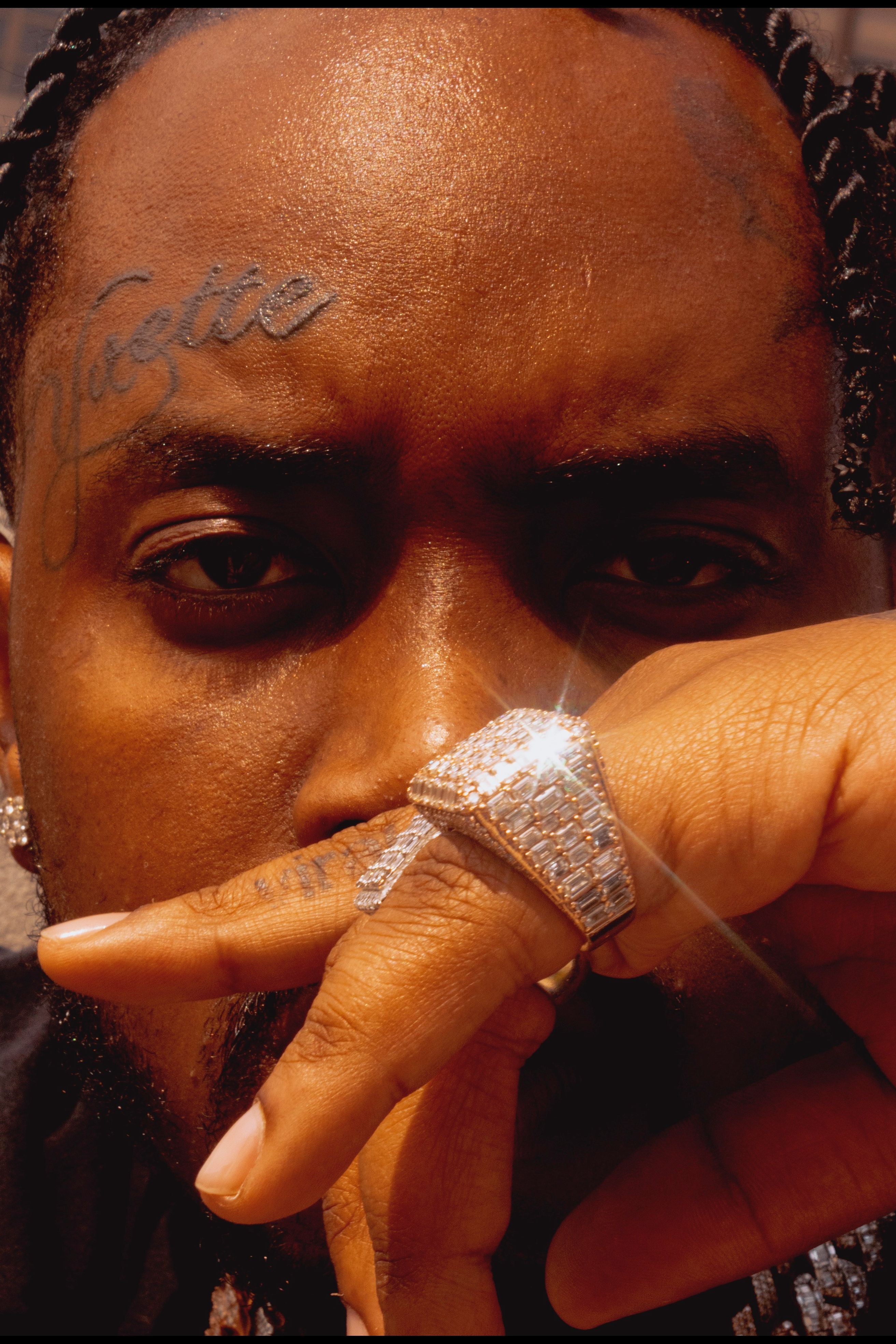

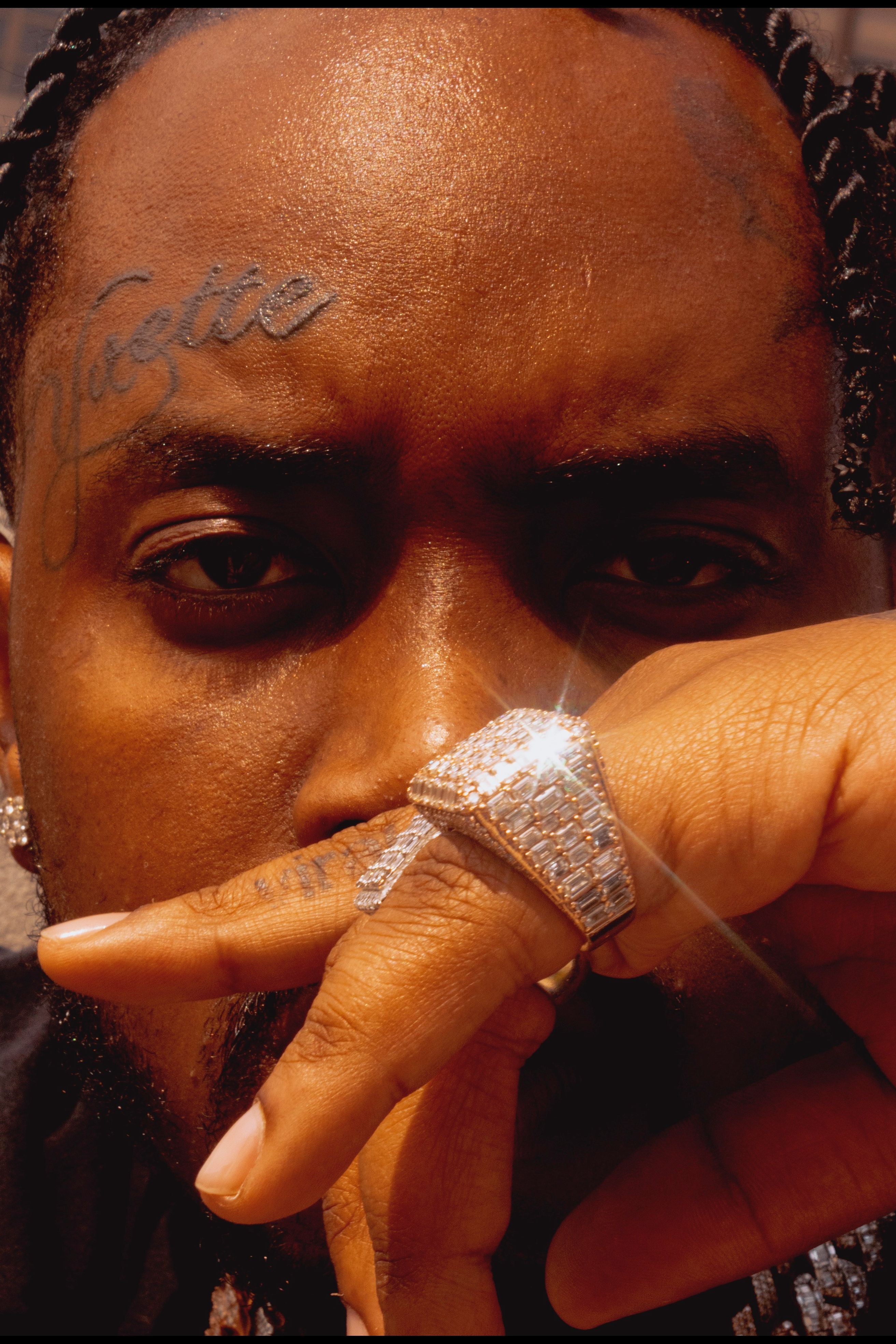

24, Flatbush

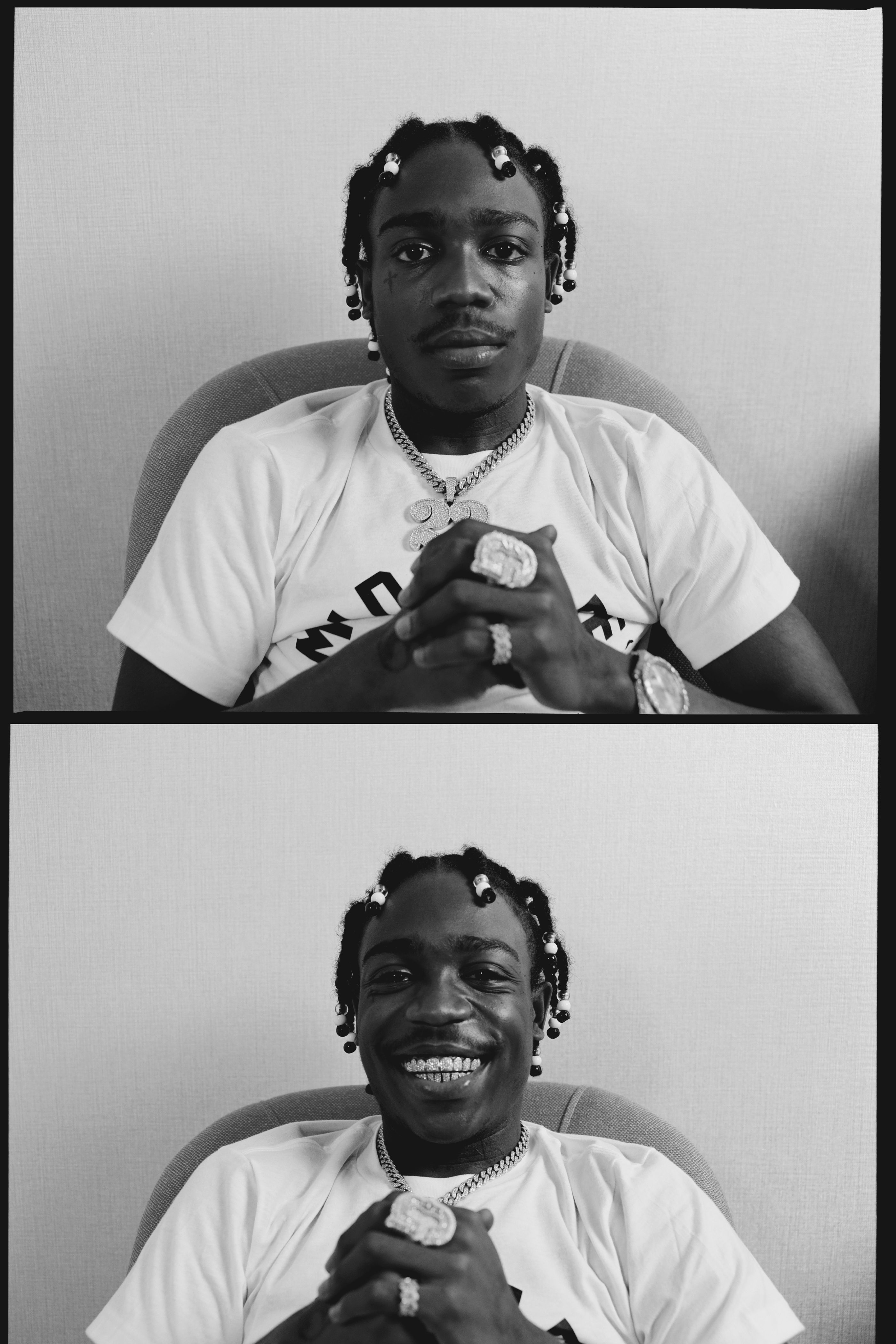

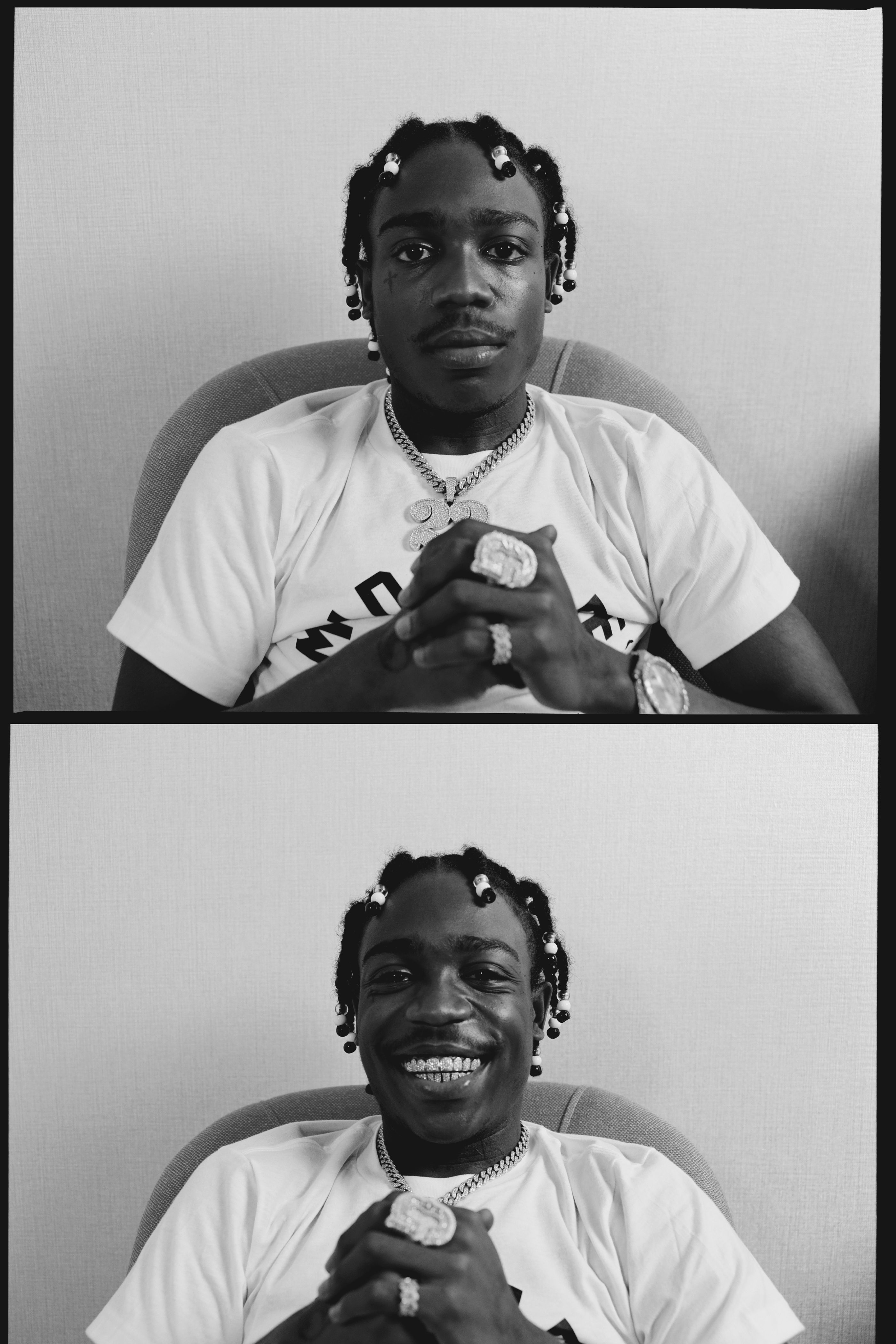

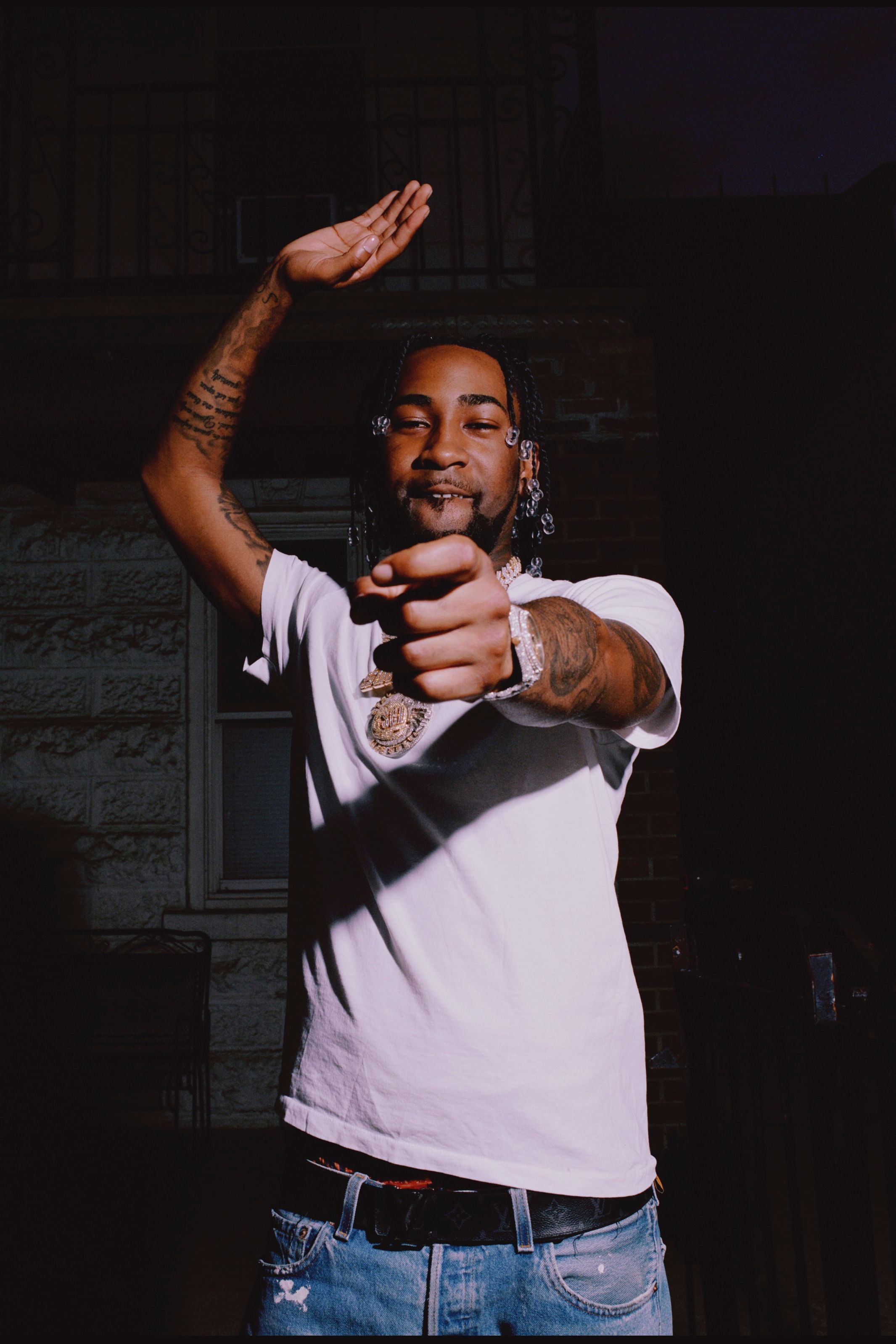

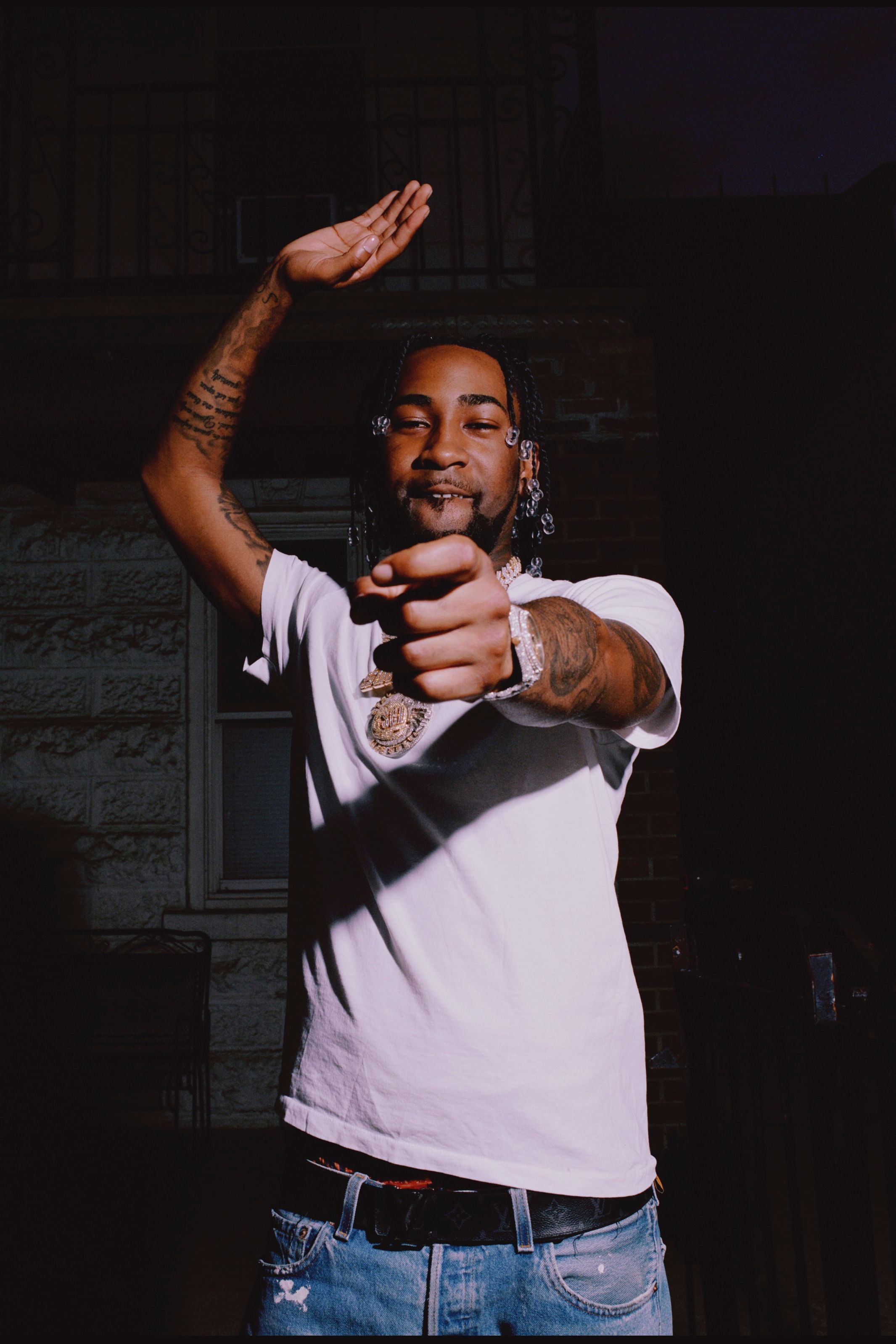

➼ 22Gz is credited with helping bring the U.K. scene’s dancier style to Brooklyn. With a long history of police run-ins dating back to 2014, he has felt the NYPD’s crackdown on drill more than most. In 2019, he was scheduled to perform at the Rolling Loud festival in Queens when he was shut out at the last minute by police, who said he was associated with “public-safety concerns.”

➼ This June, as he arrived at JFK to perform at Hot 97’s Summer Jam festival, he was arrested on attempted-murder charges for a March shooting at a Brooklyn club where three people suffered gunshot wounds. A month after that arrest, 22Gz released a new single, “Sniper Gang Freestyle Pt. 2.”

It was our time to shine. Everybody was looking for the next Jadakiss or Meek Mill type, and it was like a little competition in the hood. I needed something that was going to make people want to move their bodies. The beats I pick give you goose bumps. They’re dark and deep and hit hard, but you could dance to them and still get that gangster feeling. Once this sound clicked and my first song got a million views, I knew I had my own lane. Eventually, all of Brooklyn got onto this sound. Now I see all five boroughs rapping like that.

Rapping saved me. I’m not saying I’d be a criminal out here in these streets, but without it, I don’t know what I’d be doing. With rap, I live how I want to live. I got my own apartment; what my mom makes in a month doesn’t add up to my rent. I know y’all know New York City is expensive. I got my own car. Rap elevated my life way faster and opened my eyes to the whole world, not just one neighborhood. I’m touring, traveling. Those little checks I was getting as a kid through YouTube and TuneCore saved my life completely.

I know over 20, 30 rappers who got signed just through this sound alone. Some of these kids don’t leave their block. They don’t go to school. They don’t leave their neighborhood. They don’t see nothing but that. I know a lot of kids in the ghetto who love recording in the studio. That’s all they want to do, and it’s probably the only positive thing they’re doing the whole year. When I was coming up, we didn’t have that access. We was all trying to be ball-players, and not everyone can. Anybody could write some bars — it’s like poetry.

There are some people who don’t take the craft seriously, and they just use the drill sound to go at their enemies or say crazy stuff. And then there’s people who actually love rap, who want to get signed, and the reason they’re doing this is all for money and for a deal to better their family. I’m not going to say drill wasn’t made for dissing, but it wasn’t made for violence. It’s just another route for the ghetto — for us in New York City — to speak how we want to talk, and let the world know how we feel, without sounding like everybody else.

24, South Bronx

➼ The rapper and producer established himself in the local drill scene by introducing something new to it: beats that heavily sample everything from ’90s R&B hits to gospel.

Mayor Adams must really have something against gang violence, so of course he’s going to use drill music to connect it to that. It’s what’s in, what’s hot. I feel like they really want to lock these people up, so now they use lyrics in court. I’m 24 years old, so I already know, but these kids are young, like 16, 17. They’re not like, “Let me watch what I say because the police will probably lock me up.” They probably think they’re so slick they can say whatever they want and then pretty soon they’re locked up.

This whole generation is a clout era. Everybody wants to look like the man, do the crazier diss. One person will say something about the other person; next thing you know, the other person is making a song about that person, and no one knows what’s real. The fans are waiting for the other person to respond. Whatever these two had going on could’ve been cool, they could’ve never even seen each other in real life, but now it’s like, “All right, bet. Once I see you, it got to be up now because we’re making songs about each other.”

They really want to crack down on drill music, but you can’t stop people from saying what they want to say. We see the little games the NYPD plays. Somebody has a show and then it gets canceled by the police at the last minute. That can really discourage a person, like, “Nah, I don’t even want to rap no more if they’re going to keep doing this.”

20, East New York

➼ Young Devyn is a relative newcomer to the Brooklyn drill scene, but she is already a music-industry veteran. She was born and raised in Brooklyn by Trinidadian parents and began singing soca music at 8 years old; by 12, she was performing in shows across the Caribbean. When she returned to New York at around 16, she pivoted to rap, inspired in part by Nicki Minaj and their shared Trini roots.

One thing about me: You’ll never see me dissing on the internet. I don’t argue on social media; I don’t highlight certain people who have passed away in my music. That’s what’s made me transcend: I stay out the way, and it’s respected so far. I was just on the block with my friends chilling, and now they hear me on the radio. That motivates people. That shows them, “Yo, we could all make it out. Even if it’s 50 of us rapping, at least one of us will.”

If we really think about it, drill music is just a lot of pain — we just want to talk about it in a way that gives us some type of enjoyment and escape for a little bit. That’s why it’s crazy to blame drill for things that didn’t start yesterday. In order for me to rap about something, it would’ve had to happen, unless we’re all just lying. These kids who already got problems with each other, they’ve had problems before they was rapping. So you’ve got to start with the community and physically make changes. And that’s not by indicting everybody every two seconds.

Instead of worrying about the music, change the kids’ actual environment. Everybody wants to be a rapper, so put some studios in the hood, have these kids rap, have them do something they want. They got to let out things that already have happened.

A lot of these drill rappers are really good people. When you’re a rapper and when you come from a certain type of environment, even though you don’t owe anybody anything, you feel like you have a responsibility. It’s not like pop or R&B — when you rap, you are a voice for a community. So when you make it out, you feel like you got to be able to work hard to be able to put people in better positions. We are out here just trying to work and employ our friends, live our life, buy jewelry, and have fun. We’re able to use our pain to make some diamonds.

18, The Bronx

➼ Kenzo B may be new to rap, but she has already earned the respect of industry peers including Fivio Foreign, Maino, and her friend Young Devyn.

—Kenzo B

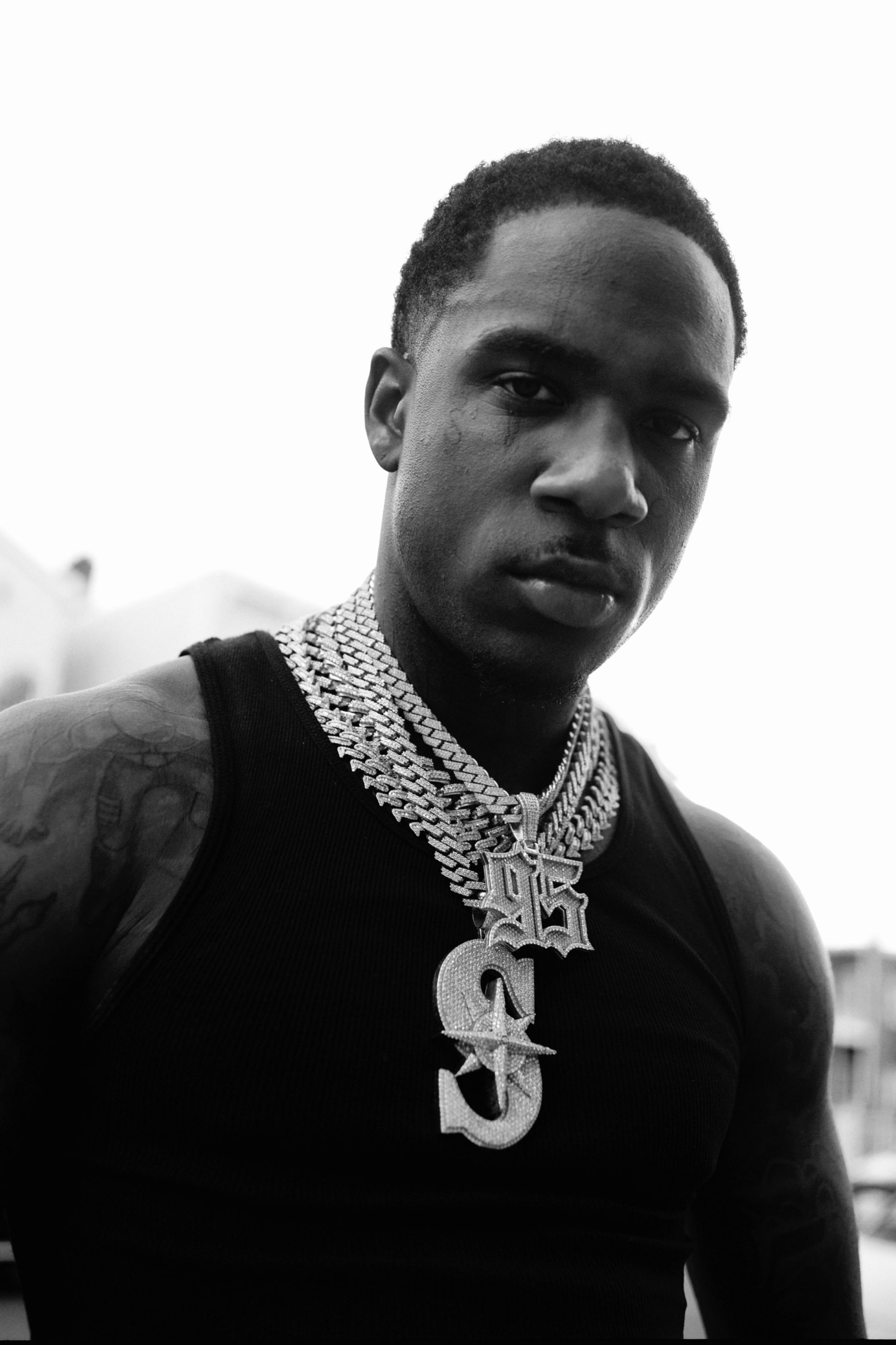

24, Flatbush

➼ 22Gz is credited with helping bring the U.K. scene’s dancier style to Brooklyn. With a long history of police run-ins dating back to 2014, he has felt the NYPD’s crackdown on drill more than most. In 2019, he was scheduled to perform at the Rolling Loud festival in Queens when he was shut out at the last minute by police, who said he was associated with “public-safety concerns.”

➼ This June, as he arrived at JFK to perform at Hot 97’s Summer Jam festival, he was arrested on attempted-murder charges for a March shooting at a Brooklyn club where three people suffered gunshot wounds. A month after that arrest, 22Gz released a new single, “Sniper Gang Freestyle Pt. 2.”

It was our time to shine. Everybody was looking for the next Jadakiss or Meek Mill type, and it was like a little competition in the hood. I needed something that was going to make people want to move their bodies. The beats I pick give you goose bumps. They’re dark and deep and hit hard, but you could dance to them and still get that gangster feeling. Once this sound clicked and my first song got a million views, I knew I had my own lane. Eventually, all of Brooklyn got onto this sound. Now I see all five boroughs rapping like that.

Rapping saved me. I’m not saying I’d be a criminal out here in these streets, but without it, I don’t know what I’d be doing. With rap, I live how I want to live. I got my own apartment; what my mom makes in a month doesn’t add up to my rent. I know y’all know New York City is expensive. I got my own car. Rap elevated my life way faster and opened my eyes to the whole world, not just one neighborhood. I’m touring, traveling. Those little checks I was getting as a kid through YouTube and TuneCore saved my life completely.

I know over 20, 30 rappers who got signed just through this sound alone. Some of these kids don’t leave their block. They don’t go to school. They don’t leave their neighborhood. They don’t see nothing but that. I know a lot of kids in the ghetto who love recording in the studio. That’s all they want to do, and it’s probably the only positive thing they’re doing the whole year. When I was coming up, we didn’t have that access. We was all trying to be ball-players, and not everyone can. Anybody could write some bars — it’s like poetry.

There are some people who don’t take the craft seriously, and they just use the drill sound to go at their enemies or say crazy stuff. And then there’s people who actually love rap, who want to get signed, and the reason they’re doing this is all for money and for a deal to better their family. I’m not going to say drill wasn’t made for dissing, but it wasn’t made for violence. It’s just another route for the ghetto — for us in New York City — to speak how we want to talk, and let the world know how we feel, without sounding like everybody else.

24, South Bronx

➼ The rapper and producer established himself in the local drill scene by introducing something new to it: beats that heavily sample everything from ’90s R&B hits to gospel.

Mayor Adams must really have something against gang violence, so of course he’s going to use drill music to connect it to that. It’s what’s in, what’s hot. I feel like they really want to lock these people up, so now they use lyrics in court. I’m 24 years old, so I already know, but these kids are young, like 16, 17. They’re not like, “Let me watch what I say because the police will probably lock me up.” They probably think they’re so slick they can say whatever they want and then pretty soon they’re locked up.

This whole generation is a clout era. Everybody wants to look like the man, do the crazier diss. One person will say something about the other person; next thing you know, the other person is making a song about that person, and no one knows what’s real. The fans are waiting for the other person to respond. Whatever these two had going on could’ve been cool, they could’ve never even seen each other in real life, but now it’s like, “All right, bet. Once I see you, it got to be up now because we’re making songs about each other.”

They really want to crack down on drill music, but you can’t stop people from saying what they want to say. We see the little games the NYPD plays. Somebody has a show and then it gets canceled by the police at the last minute. That can really discourage a person, like, “Nah, I don’t even want to rap no more if they’re going to keep doing this.”

20, East New York

➼ Young Devyn is a relative newcomer to the Brooklyn drill scene, but she is already a music-industry veteran. She was born and raised in Brooklyn by Trinidadian parents and began singing soca music at 8 years old; by 12, she was performing in shows across the Caribbean. When she returned to New York at around 16, she pivoted to rap, inspired in part by Nicki Minaj and their shared Trini roots.

One thing about me: You’ll never see me dissing on the internet. I don’t argue on social media; I don’t highlight certain people who have passed away in my music. That’s what’s made me transcend: I stay out the way, and it’s respected so far. I was just on the block with my friends chilling, and now they hear me on the radio. That motivates people. That shows them, “Yo, we could all make it out. Even if it’s 50 of us rapping, at least one of us will.”

If we really think about it, drill music is just a lot of pain — we just want to talk about it in a way that gives us some type of enjoyment and escape for a little bit. That’s why it’s crazy to blame drill for things that didn’t start yesterday. In order for me to rap about something, it would’ve had to happen, unless we’re all just lying. These kids who already got problems with each other, they’ve had problems before they was rapping. So you’ve got to start with the community and physically make changes. And that’s not by indicting everybody every two seconds.

Instead of worrying about the music, change the kids’ actual environment. Everybody wants to be a rapper, so put some studios in the hood, have these kids rap, have them do something they want. They got to let out things that already have happened.

A lot of these drill rappers are really good people. When you’re a rapper and when you come from a certain type of environment, even though you don’t owe anybody anything, you feel like you have a responsibility. It’s not like pop or R&B — when you rap, you are a voice for a community. So when you make it out, you feel like you got to be able to work hard to be able to put people in better positions. We are out here just trying to work and employ our friends, live our life, buy jewelry, and have fun. We’re able to use our pain to make some diamonds.

18, The Bronx

➼ Kenzo B may be new to rap, but she has already earned the respect of industry peers including Fivio Foreign, Maino, and her friend Young Devyn.

—Kenzo B

29, East New York

➼ Brooklyn’s Envy Caine is a classic case of increased exposure as a drill rapper coming at a price. Earlier this year, prosecutors charged that there had been an ongoing plot against his life for six years, stemming from an alleged beef with some members of a New York gang. Meanwhile, he says, having extra NYPD eyes on him had stunted his career well before his current incarceration on gun charges.

Not pictured. Envy Caine is currently on Rikers Island.

It’s really rare for popular drill artists to get a chance to perform and make money to feed their kids because the police automatically say, “Oh, they can’t perform due to gang violence.” I can’t put on shows in New York, period. Artists are trying to progress their careers, and they’ll never reach their pinnacle surrounded by cops. Half the time, they don’t even know the artist; they just hear what kind of artist.

Not pictured. Envy Caine is currently on Rikers Island.

These songs just have an aggression to them that if you don’t understand what’s going on, you will perceive it as, Oh, this is making violence happen. Now, I’m not saying it’s innocent, either, but that’s more to do with what people are already getting into.

I’m a workaholic. I try to stay out of anything negative and just lock myself in the studio. I do ten-hour sessions to keep myself busy. That’s why I’m still releasing music twice a month while I’ve been locked up for a year. Staying focused is my motivation. I want us—drill—to be respected as a real genre of music.

Not pictured. Envy Caine is currently on Rikers Island.

32, East Flatbush

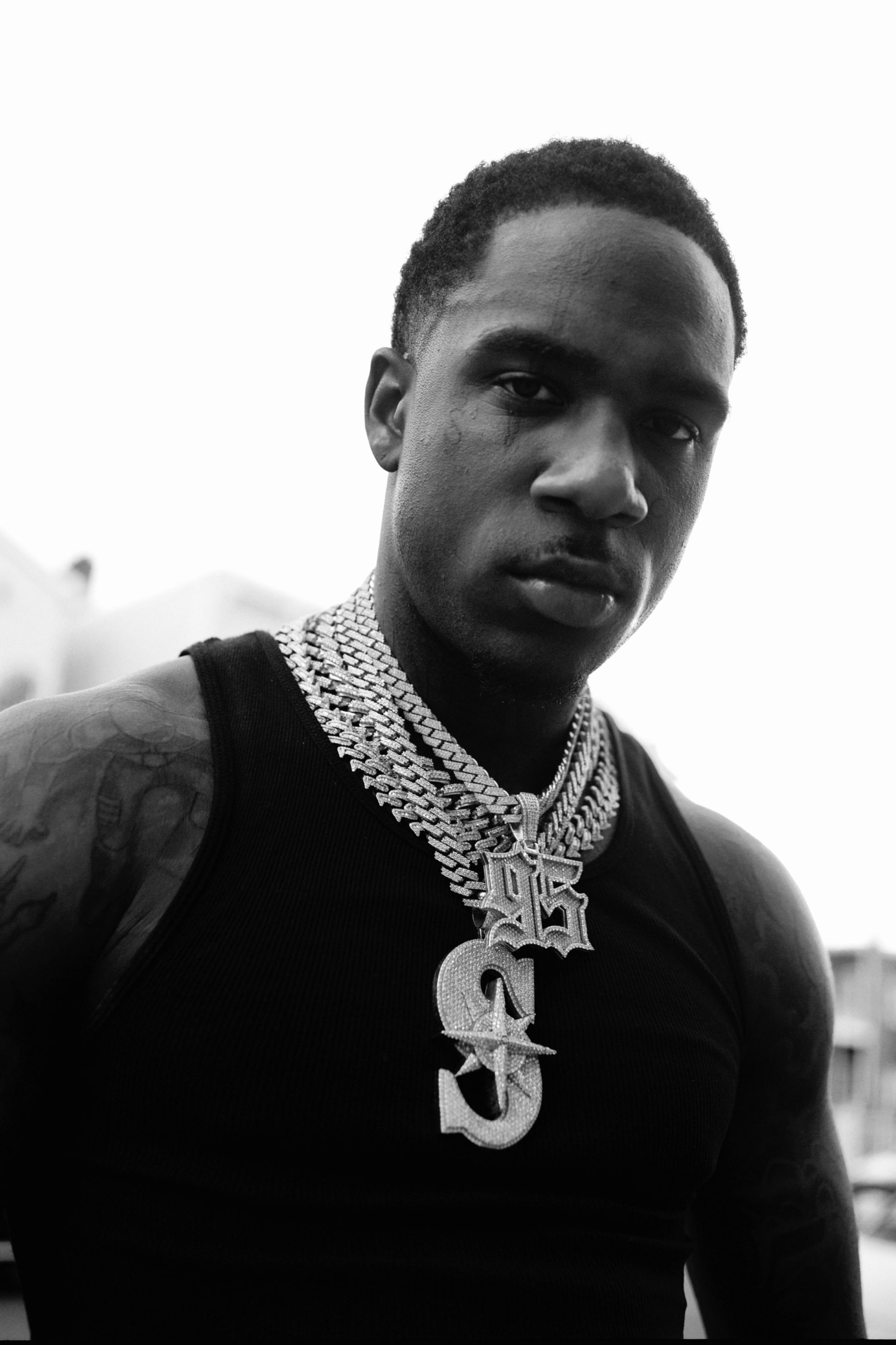

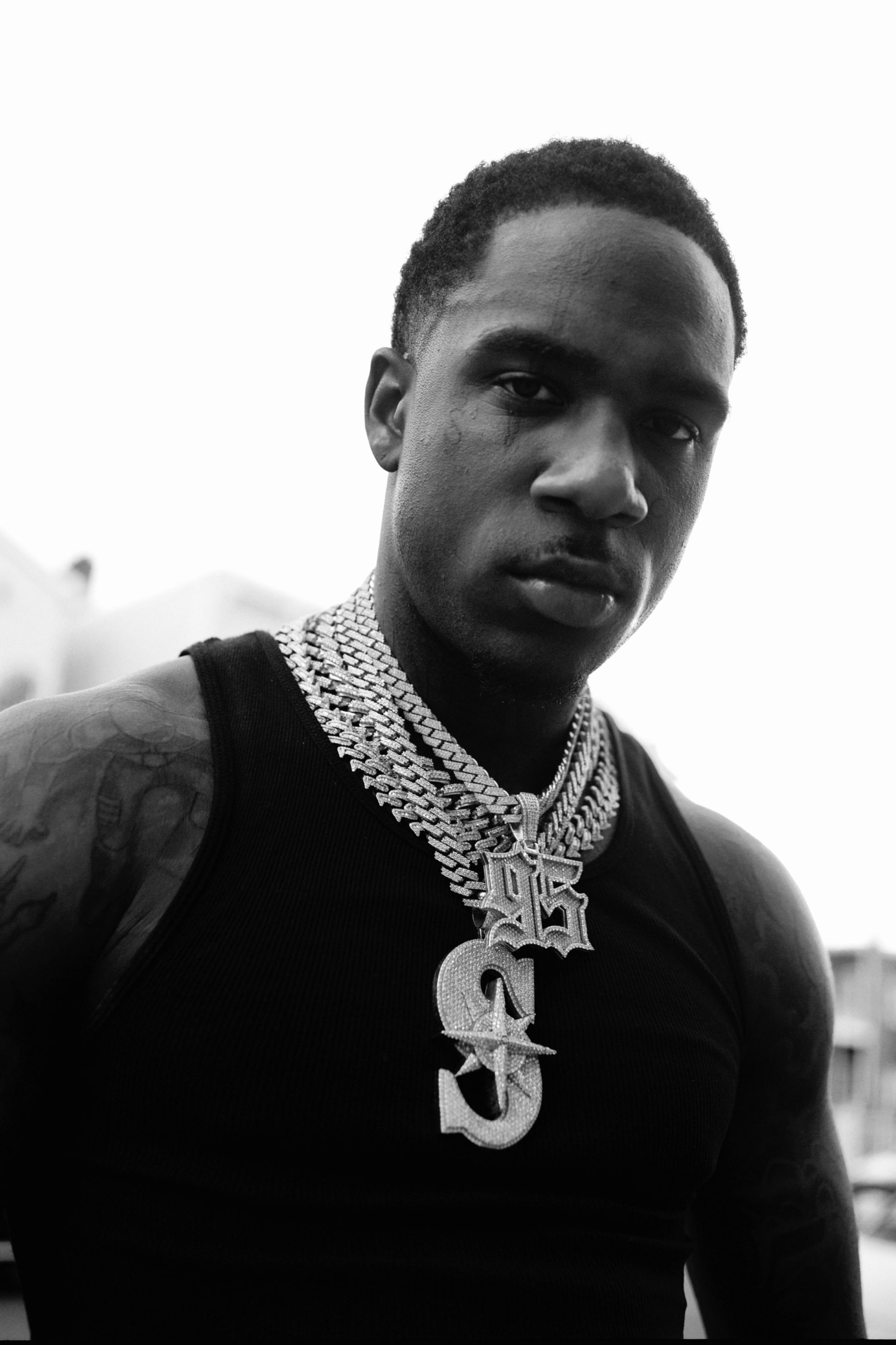

➼ If there’s a face of New York rap right now, it’s Fivio Foreign. His first hit, “Big Drip,” went viral in 2019, prompting a remix with Lil Baby and Quavo. This year’s “City of Gods,” featuring Ye and Alicia Keys, has been blaring from car speakers and block parties around the city. He has become an ambassador for New York drill, attending the February “summit” the mayor held with local rappers to discuss violence as it relates to the music.

It’s a shame the way the whole genre gets portrayed. You can’t just put it on drill like we’re the only people talking about a gun or death. I guess with drill, you can kind of understand the lyrics in a more literal way than a lot of other styles, so people notice it more. But it just don’t make no sense. I get called to perform at bar mitzvahs, and these kids know all the music and all the words and it don’t persuade them to do nothing violent.

You can almost compare it to a movie or a book that tells a story of selling drugs. We watch Boyz n the Hood and Training Day, but we don’t lock up the director. We don’t lock up the Denzel Washingtons. I don’t know what makes a music video different.

The genre is always expanding, and it’s because of the innovators. Sample drill wouldn’t be possible without Pop Smoke, period. The whole point of my latest album was about expanding drill. I got songs with Alicia Keys, KayCyy, Chloe Bailey, Chris Brown — people you wouldn’t expect to be on drill beats. Expanding my content helps drill get bigger instead of keeping it in a bubble with people looking at it as new-school gangster rap.

23, East New York

➼ Since dropping his first single, “Don’t Start,” three years ago, Bizzy Banks has cemented his place as one of the leading NY drill rappers. That momentum has been halted by arrests, first in 2019 on assault charges and again in January of this year on drugs and weapons charges.

Not pictured. Bizzy Banks was released from Rikers Island on August 11.

Every drill rapper is not gangster, just like every regular rapper is not gangster. Every drill rapper doesn’t smoke people; every drill rapper doesn’t antagonize other people. We’re creating dance moves; we’re creating new words. I don’t rap about things they say we rap about. I’m looking forward to going mainstream, to get out of the box of being a drill rapper, so I won’t be targeted. I could do bigger shows in the city without being bugged by or shut down by police.

Not pictured. Bizzy Banks was released from Rikers Island on August 11.

—Bizzy Banks

Not pictured. Bizzy Banks was released from Rikers Island on August 11.

27, Harlem and The Bronx

➼ The rapper who grew up all over New York and Connecticut has carved out his niche with sounds that sample early-aughts emo and alt rock.

If you’re gonna attack the whole genre, you have to do research on the whole genre. My sound? The samples we chose were early-2000s alternative like Blink-182, Foo Fighters, Snow Patrol. It’s like, “Let’s try to make it more universal so the white kids won’t get looked weird at for banging this music, and the Black kids won’t either.” For proof, come to one of my shows. The whole crowd is full of kids. There’s no aggression. There are older people who are into my music. I never had a fight at none of my shows.

—Polo Perks

24, South Jamaica

➼ Along with Shawny Binladen and the rest of his Yellow Tape Boyz crew, Big Yaya holds it down for Queens in a genre dominated by rappers from Brooklyn and the Bronx.

—Big Yaya

29, East New York

➼ Brooklyn’s Envy Caine is a classic case of increased exposure as a drill rapper coming at a price. Earlier this year, prosecutors charged that there had been an ongoing plot against his life for six years, stemming from an alleged beef with some members of a New York gang. Meanwhile, he says, having extra NYPD eyes on him had stunted his career well before his current incarceration on gun charges.

Not pictured. Envy Caine is currently on Rikers Island.

It’s really rare for popular drill artists to get a chance to perform and make money to feed their kids because the police automatically say, “Oh, they can’t perform due to gang violence.” I can’t put on shows in New York, period. Artists are trying to progress their careers, and they’ll never reach their pinnacle surrounded by cops. Half the time, they don’t even know the artist; they just hear what kind of artist.

Not pictured. Envy Caine is currently on Rikers Island.

These songs just have an aggression to them that if you don’t understand what’s going on, you will perceive it as, Oh, this is making violence happen. Now, I’m not saying it’s innocent, either, but that’s more to do with what people are already getting into.

I’m a workaholic. I try to stay out of anything negative and just lock myself in the studio. I do ten-hour sessions to keep myself busy. That’s why I’m still releasing music twice a month while I’ve been locked up for a year. Staying focused is my motivation. I want us—drill—to be respected as a real genre of music.

Not pictured. Envy Caine is currently on Rikers Island.

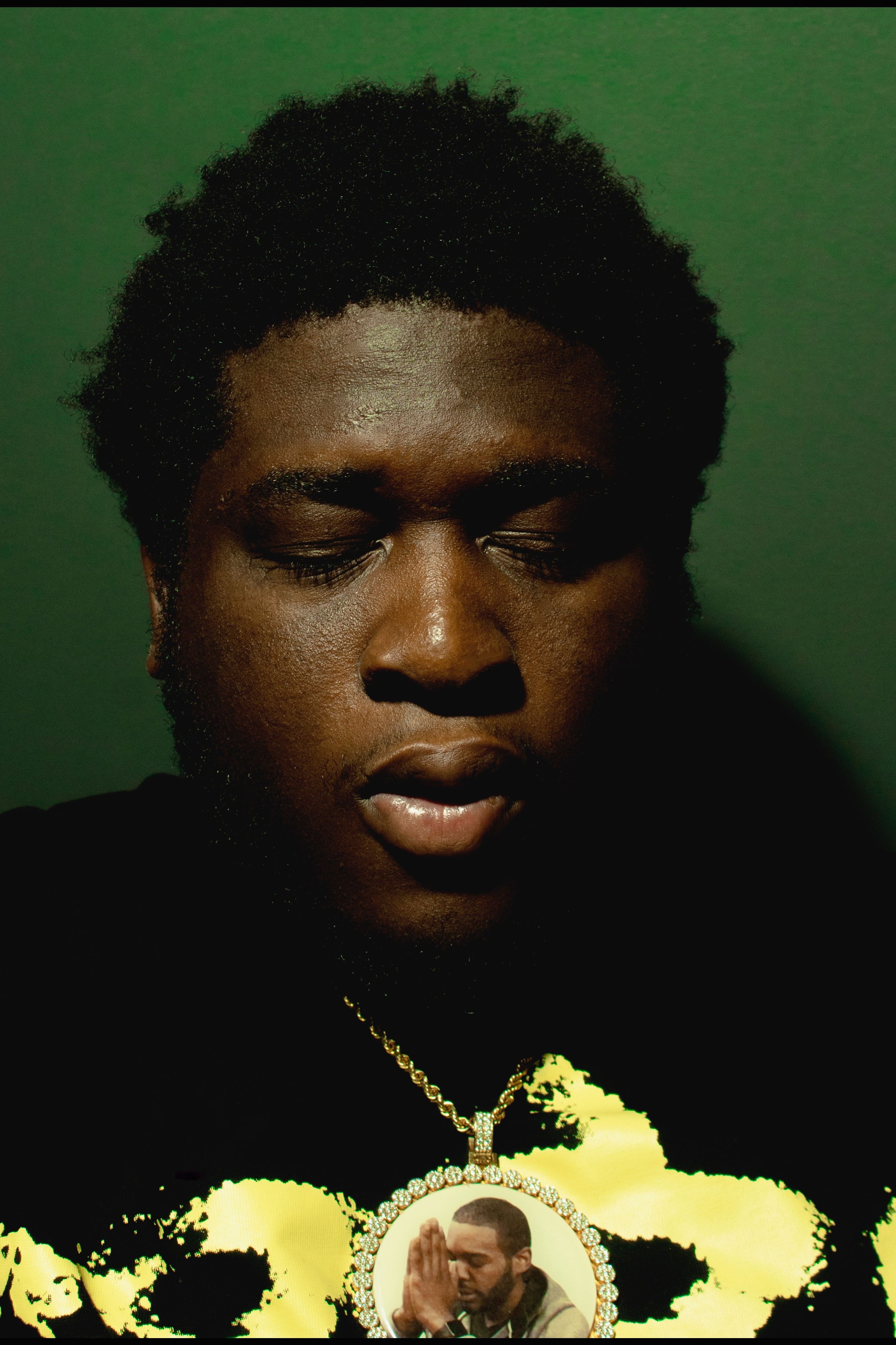

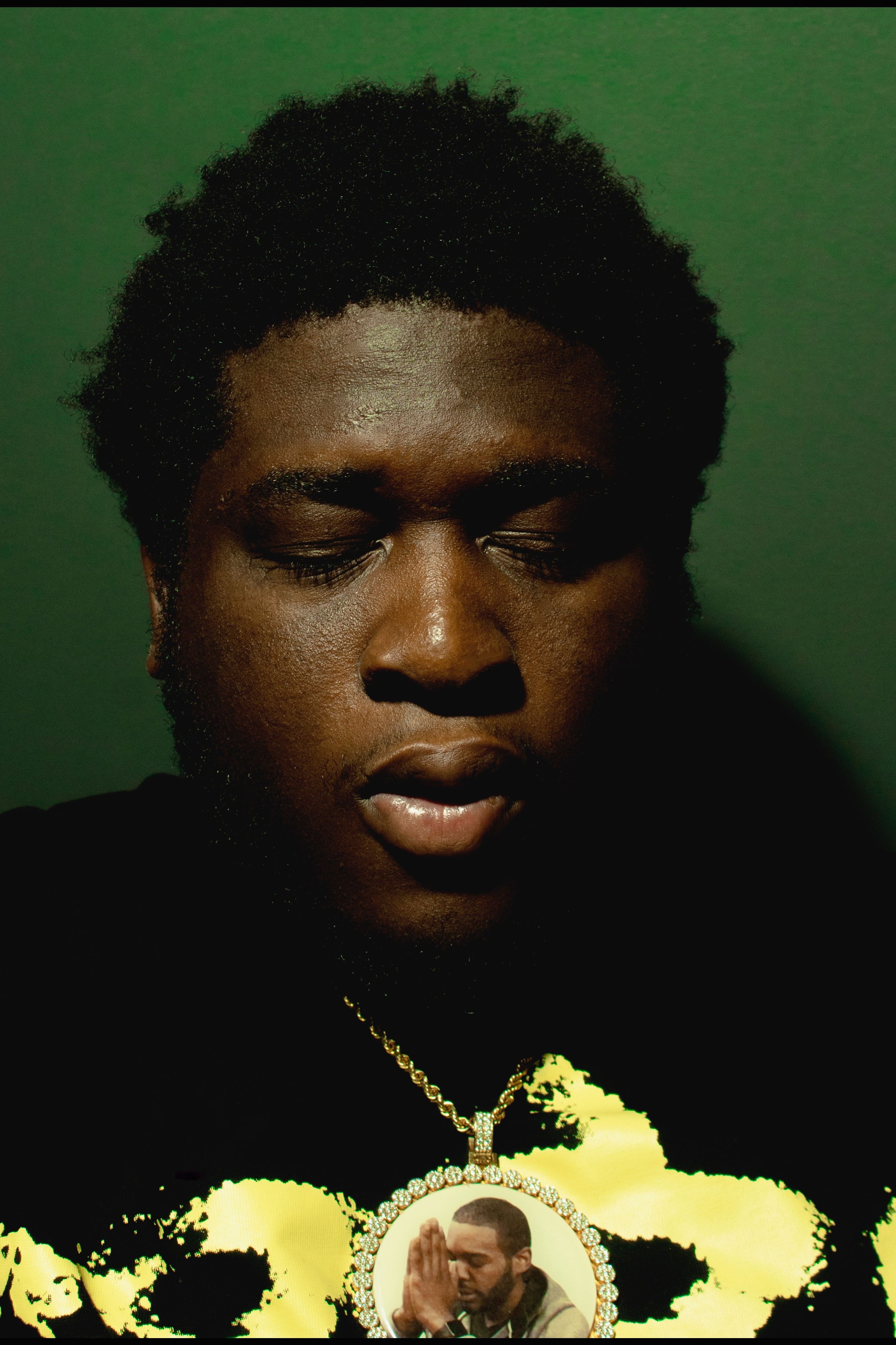

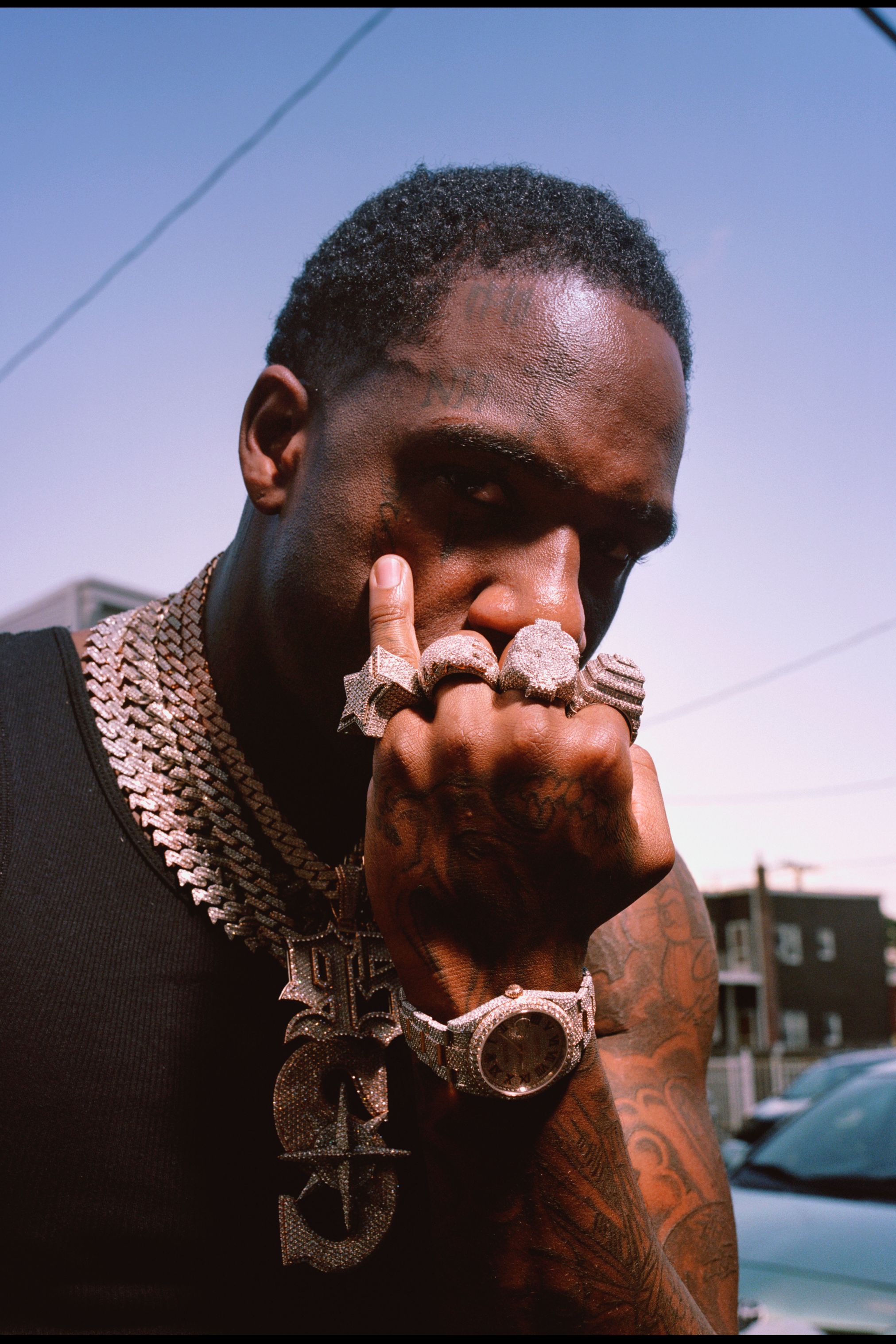

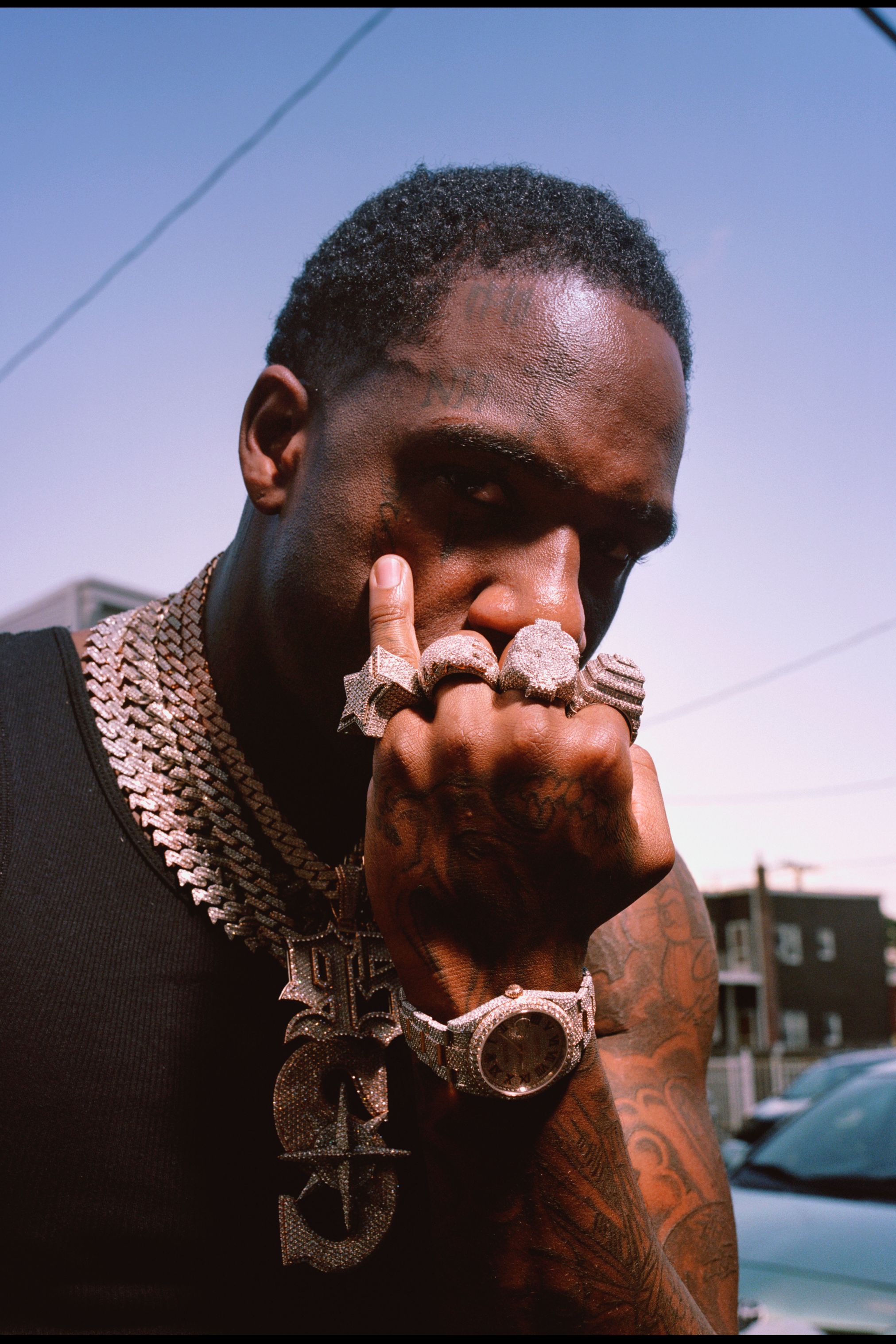

32, East Flatbush

➼ If there’s a face of New York rap right now, it’s Fivio Foreign. His first hit, “Big Drip,” went viral in 2019, prompting a remix with Lil Baby and Quavo. This year’s “City of Gods,” featuring Ye and Alicia Keys, has been blaring from car speakers and block parties around the city. He has become an ambassador for New York drill, attending the February “summit” the mayor held with local rappers to discuss violence as it relates to the music.

It’s a shame the way the whole genre gets portrayed. You can’t just put it on drill like we’re the only people talking about a gun or death. I guess with drill, you can kind of understand the lyrics in a more literal way than a lot of other styles, so people notice it more. But it just don’t make no sense. I get called to perform at bar mitzvahs, and these kids know all the music and all the words and it don’t persuade them to do nothing violent.

You can almost compare it to a movie or a book that tells a story of selling drugs. We watch Boyz n the Hood and Training Day, but we don’t lock up the director. We don’t lock up the Denzel Washingtons. I don’t know what makes a music video different.

The genre is always expanding, and it’s because of the innovators. Sample drill wouldn’t be possible without Pop Smoke, period. The whole point of my latest album was about expanding drill. I got songs with Alicia Keys, KayCyy, Chloe Bailey, Chris Brown — people you wouldn’t expect to be on drill beats. Expanding my content helps drill get bigger instead of keeping it in a bubble with people looking at it as new-school gangster rap.

23, East New York

➼ Since dropping his first single, “Don’t Start,” three years ago, Bizzy Banks has cemented his place as one of the leading NY drill rappers. That momentum has been halted by arrests, first in 2019 on assault charges and again in January of this year on drugs and weapons charges.

Not pictured. Bizzy Banks was released from Rikers Island on August 11.

Every drill rapper is not gangster, just like every regular rapper is not gangster. Every drill rapper doesn’t smoke people; every drill rapper doesn’t antagonize other people. We’re creating dance moves; we’re creating new words. I don’t rap about things they say we rap about. I’m looking forward to going mainstream, to get out of the box of being a drill rapper, so I won’t be targeted. I could do bigger shows in the city without being bugged by or shut down by police.

Not pictured. Bizzy Banks was released from Rikers Island on August 11.

—Bizzy Banks

Not pictured. Bizzy Banks was released from Rikers Island on August 11.

27, Harlem and The Bronx

➼ The rapper who grew up all over New York and Connecticut has carved out his niche with sounds that sample early-aughts emo and alt rock.

If you’re gonna attack the whole genre, you have to do research on the whole genre. My sound? The samples we chose were early-2000s alternative like Blink-182, Foo Fighters, Snow Patrol. It’s like, “Let’s try to make it more universal so the white kids won’t get looked weird at for banging this music, and the Black kids won’t either.” For proof, come to one of my shows. The whole crowd is full of kids. There’s no aggression. There are older people who are into my music. I never had a fight at none of my shows.

—Polo Perks

24, South Jamaica

➼ Along with Shawny Binladen and the rest of his Yellow Tape Boyz crew, Big Yaya holds it down for Queens in a genre dominated by rappers from Brooklyn and the Bronx.

—Big Yaya

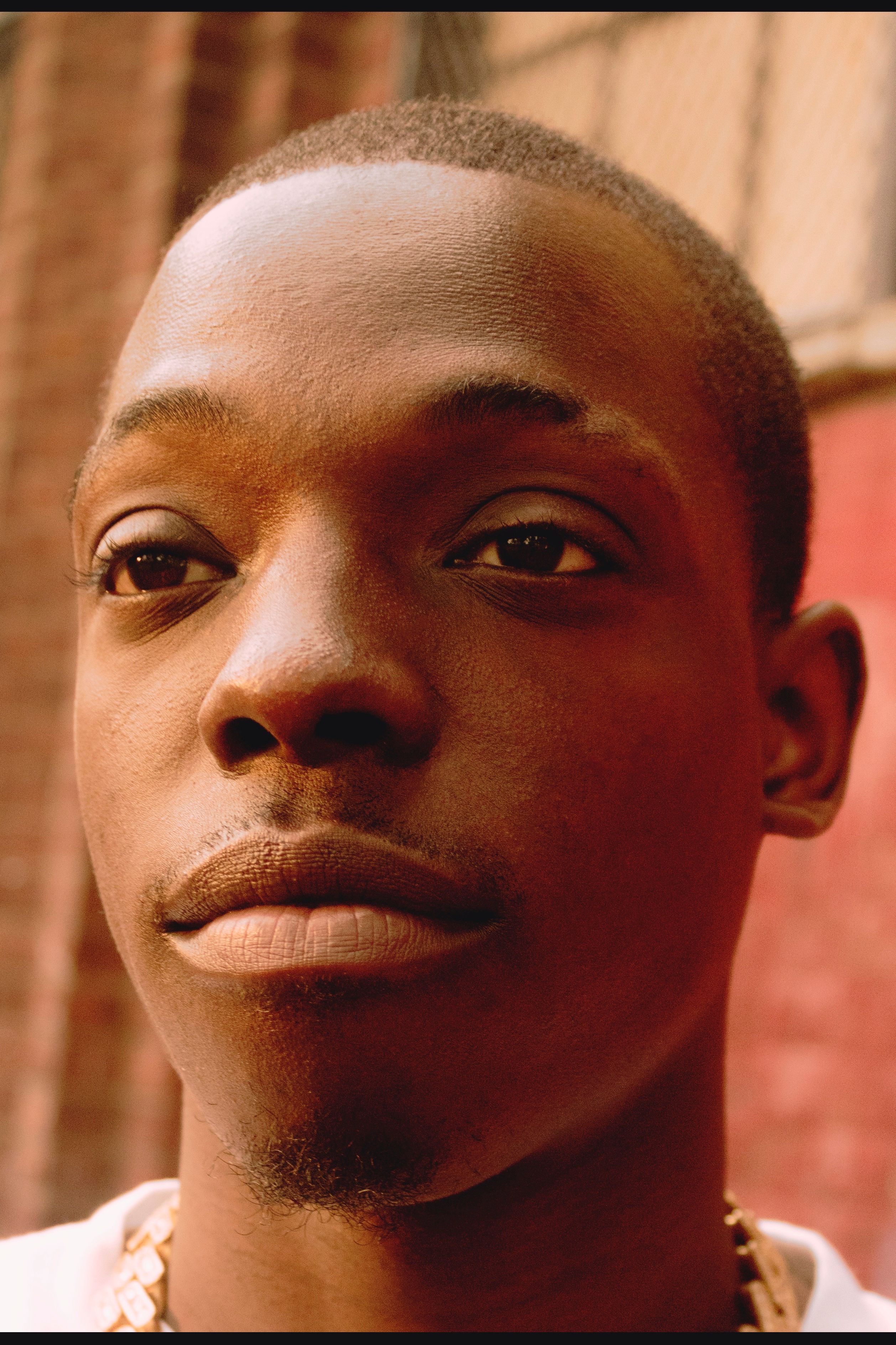

28, East Flatbush

➼ In 2014, well before the genre exploded in New York, Bobby Shmurda, then a newcomer out of East Flatbush, embodied the image of a drill rapper. His viral behemoth “Hot Nigga” launched a million memes and led to a record deal. As his profile grew, police investigated Shmurda’s GS9 crew, pointing to his lyrics as evidence of criminal activity.

➼ He was arrested in 2014 on gun charges and served six years in prison. While often credited with the rise of drill in Brooklyn, he doesn’t consider himself a drill artist. Now a year out from prison, Shmurda has returned to music unsigned and is experimenting with new sounds.

I’m 28 and I feel like I’m 19. Ever since getting out, life has been a roller coaster. I’ve been enjoying life, but I’ve also been trying to get my music into my own hands. The company I was with kept control of everything before I came out. So now I’m trying to release my stuff independently and own it.

Drill is a category I don’t want to be. The stereotypes about it are coming from the people pushing the narratives. If it’s all about gangster rap and shooting things up, then why the fuck are rappers onstage performing? They should have no time for that if the perception was real.

When they see us, I don’t want them to think of just drill. If I wanna sing, I’ll sing. I embrace the past because the past is the future. It’s the way I learned all my lessons. I understand everything that any ghetto kid goes through because I’ve been through everything in the ghetto, through group homes and all that. In the hood, I get the only feedback that matters: They say, “Oh shit, when you say it like that, I understand. You’re talking my language.”

30, East Flatbush

➼ At 30, Rowdy Rebel has been in the game long enough to be considered one of the elders of the scene. He rose to prominence in East Flatbush alongside Bobby Shmurda in the mid-2010s, only to miss out on the rest of the decade during a six-year sentence owed in part to GS9’s sudden fame. He returned with this year’s Rebel vs. Rowdy, his first album since his release from prison in 2021.

—Rowdy Rebel

23, Crown Heights

➼ The Crown Heights native picked up rapping while in prison on gang-conspiracy charges. He released “Aaron Rodgers,” an autobiographical song paying homage to the football star, the week after he was released in 2019. In July, he dropped an album on Def Jam.

The police once locked me up for a situation that had to do with one of my music videos. It’s a violation of our First Amendment rights as artists. The music connects with people — they feel it because everybody has emotions. I try not to make music only about violence but pain and sadness, too, because I know everybody could relate to it.

21, Crown Heights

➼ Growing up in Crown Heights, Eli Fross wanted to be a pro basketball player. He played for a travel league as a teenager but fell away from the sport when he got caught up with guys in his neighborhood “doing shit I wasn’t supposed to be,” he says. Getting into rapping helped him refocus and earned him an RCA record deal by the age of 19. Now 21, he’s a member of the Winners Circle cohort with Sheff G and Sleepy Hallow (the latter could not be reached while incarcerated).

Sometimes I would wake up in the studio saying, I’m not feeling it — I’m depressed, I’m angry, or whatever — and I would rap off that energy. Eventually, as I got older and deeper into rap, I had more to lose. So it’s like I had to put things away in order to keep growing and doing what I love. The NYPD is basically saying they don’t want us to grow; they don’t want us to be better people. I ain’t come up on no nine-to-five job — none of that. I was doing this. It’s my way out.

This music has helped a lot of people, and they know that — they know this is the way for us to come together as a community. Me and Sheff, for example, we will always fuck with each other, but the music made the bond way stronger. We know there’s a lot of negativity around the music we put out, but we don’t let that trick us out the game. We don’t only put out drill music; we artists now. A drill rapper is what I started as. It’s not what I’m going to end as.

23, Flatbush

➼ The video for Sheff G’s latest single, “No Remorse,” is a montage depicting a day in the life of a rapper at the top of his game: in the studio, putting on an impromptu show in a mansion with the Winners Circle, walking a goat down the sidewalk in New York. It’s a stark contrast to the 23-year-old Flatbush star’s current situation — locked up on a two-year sentence for weapons charges in a prison upstate — and the continuation of a run of prison releases culminating in his July album From the Can.

Not pictured. Sheff G is currently incarcerated.

When we started rapping, at first it was just for fun. We didn’t think nothing of it. But when we blew up and the money started coming, we learned we could feed our families. It changed everything. Why would you want to take that from us? You’re going to leave us nothing to turn to.

Not pictured. Sheff G is currently incarcerated.

People talk about drill, but they won’t take the time to really understand what we go through. They don’t want to. I was living in a shelter. I’ve got a two-year sentence right now for attempted gun possession. Now I’m upstate with people that have five years for attempted murder. How is my crime comparable to that? Obviously, there’s a targeted situation going on. Growing up in the hood, you battling shit like that on the regular. You’re always the one that’s being looked down upon. So this is nothing new to me.

Not pictured. Sheff G is currently incarcerated.

—Sheff G

Not pictured. Sheff G is currently incarcerated.

28, East Flatbush

➼ In 2014, well before the genre exploded in New York, Bobby Shmurda, then a newcomer out of East Flatbush, embodied the image of a drill rapper. His viral behemoth “Hot Nigga” launched a million memes and led to a record deal. As his profile grew, police investigated Shmurda’s GS9 crew, pointing to his lyrics as evidence of criminal activity.

➼ He was arrested in 2014 on gun charges and served six years in prison. While often credited with the rise of drill in Brooklyn, he doesn’t consider himself a drill artist. Now a year out from prison, Shmurda has returned to music unsigned and is experimenting with new sounds.

I’m 28 and I feel like I’m 19. Ever since getting out, life has been a roller coaster. I’ve been enjoying life, but I’ve also been trying to get my music into my own hands. The company I was with kept control of everything before I came out. So now I’m trying to release my stuff independently and own it.

Drill is a category I don’t want to be. The stereotypes about it are coming from the people pushing the narratives. If it’s all about gangster rap and shooting things up, then why the fuck are rappers onstage performing? They should have no time for that if the perception was real.

When they see us, I don’t want them to think of just drill. If I wanna sing, I’ll sing. I embrace the past because the past is the future. It’s the way I learned all my lessons. I understand everything that any ghetto kid goes through because I’ve been through everything in the ghetto, through group homes and all that. In the hood, I get the only feedback that matters: They say, “Oh shit, when you say it like that, I understand. You’re talking my language.”

30, East Flatbush

➼ At 30, Rowdy Rebel has been in the game long enough to be considered one of the elders of the scene. He rose to prominence in East Flatbush alongside Bobby Shmurda in the mid-2010s, only to miss out on the rest of the decade during a six-year sentence owed in part to GS9’s sudden fame. He returned with this year’s Rebel vs. Rowdy, his first album since his release from prison in 2021.

—Rowdy Rebel

23, Crown Heights

➼ The Crown Heights native picked up rapping while in prison on gang-conspiracy charges. He released “Aaron Rodgers,” an autobiographical song paying homage to the football star, the week after he was released in 2019. In July, he dropped an album on Def Jam.

The police once locked me up for a situation that had to do with one of my music videos. It’s a violation of our First Amendment rights as artists. The music connects with people — they feel it because everybody has emotions. I try not to make music only about violence but pain and sadness, too, because I know everybody could relate to it.

21, Crown Heights

➼ Growing up in Crown Heights, Eli Fross wanted to be a pro basketball player. He played for a travel league as a teenager but fell away from the sport when he got caught up with guys in his neighborhood “doing shit I wasn’t supposed to be,” he says. Getting into rapping helped him refocus and earned him an RCA record deal by the age of 19. Now 21, he’s a member of the Winners Circle cohort with Sheff G and Sleepy Hallow (the latter could not be reached while incarcerated).

Sometimes I would wake up in the studio saying, I’m not feeling it — I’m depressed, I’m angry, or whatever — and I would rap off that energy. Eventually, as I got older and deeper into rap, I had more to lose. So it’s like I had to put things away in order to keep growing and doing what I love. The NYPD is basically saying they don’t want us to grow; they don’t want us to be better people. I ain’t come up on no nine-to-five job — none of that. I was doing this. It’s my way out.

This music has helped a lot of people, and they know that — they know this is the way for us to come together as a community. Me and Sheff, for example, we will always fuck with each other, but the music made the bond way stronger. We know there’s a lot of negativity around the music we put out, but we don’t let that trick us out the game. We don’t only put out drill music; we artists now. A drill rapper is what I started as. It’s not what I’m going to end as.

23, Flatbush

➼ The video for Sheff G’s latest single, “No Remorse,” is a montage depicting a day in the life of a rapper at the top of his game: in the studio, putting on an impromptu show in a mansion with the Winners Circle, walking a goat down the sidewalk in New York. It’s a stark contrast to the 23-year-old Flatbush star’s current situation — locked up on a two-year sentence for weapons charges in a prison upstate — and the continuation of a run of prison releases culminating in his July album From the Can.

Not pictured. Sheff G is currently incarcerated.

When we started rapping, at first it was just for fun. We didn’t think nothing of it. But when we blew up and the money started coming, we learned we could feed our families. It changed everything. Why would you want to take that from us? You’re going to leave us nothing to turn to.

Not pictured. Sheff G is currently incarcerated.

People talk about drill, but they won’t take the time to really understand what we go through. They don’t want to. I was living in a shelter. I’ve got a two-year sentence right now for attempted gun possession. Now I’m upstate with people that have five years for attempted murder. How is my crime comparable to that? Obviously, there’s a targeted situation going on. Growing up in the hood, you battling shit like that on the regular. You’re always the one that’s being looked down upon. So this is nothing new to me.

Not pictured. Sheff G is currently incarcerated.

—Sheff G

Not pictured. Sheff G is currently incarcerated.

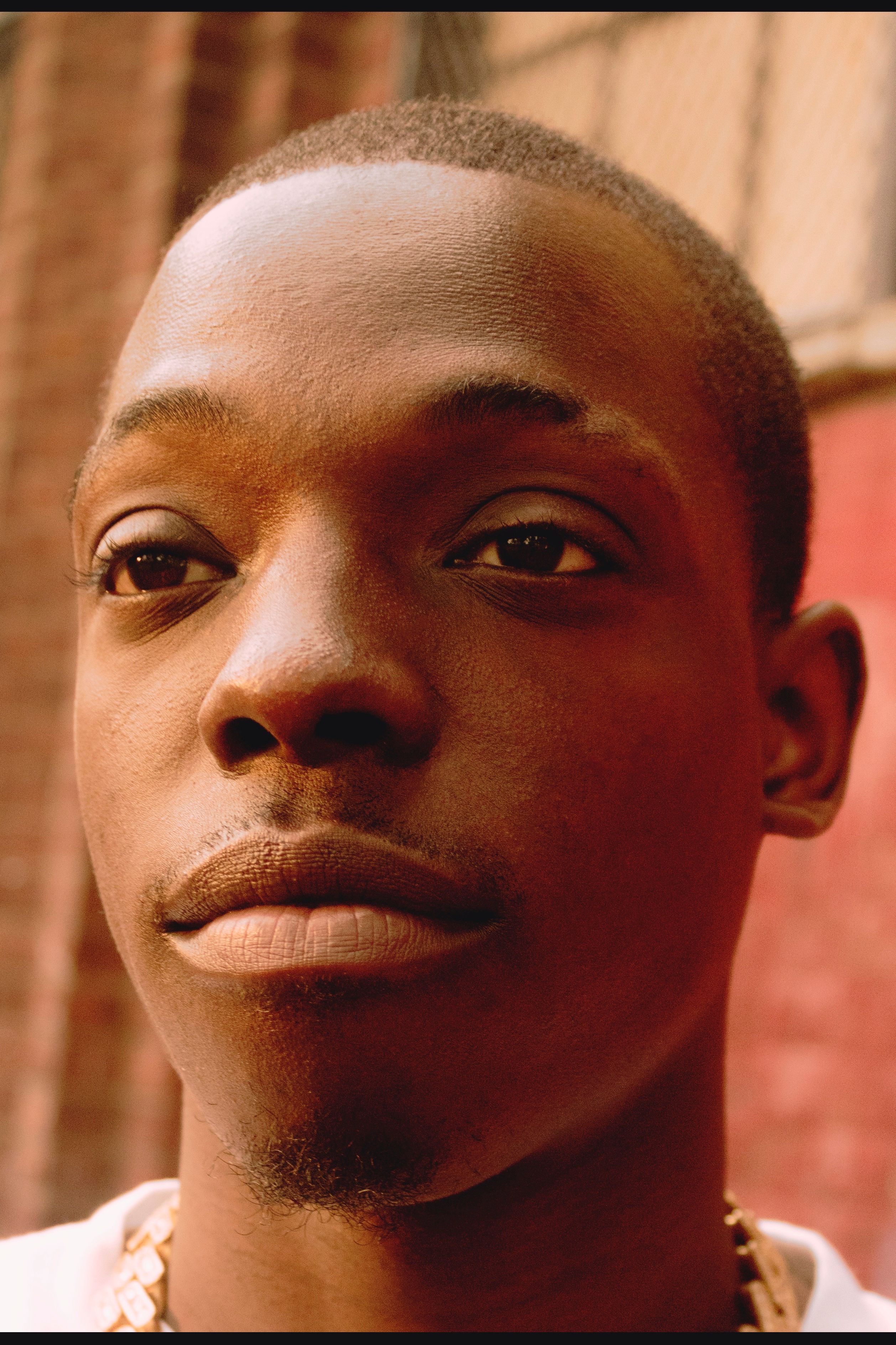

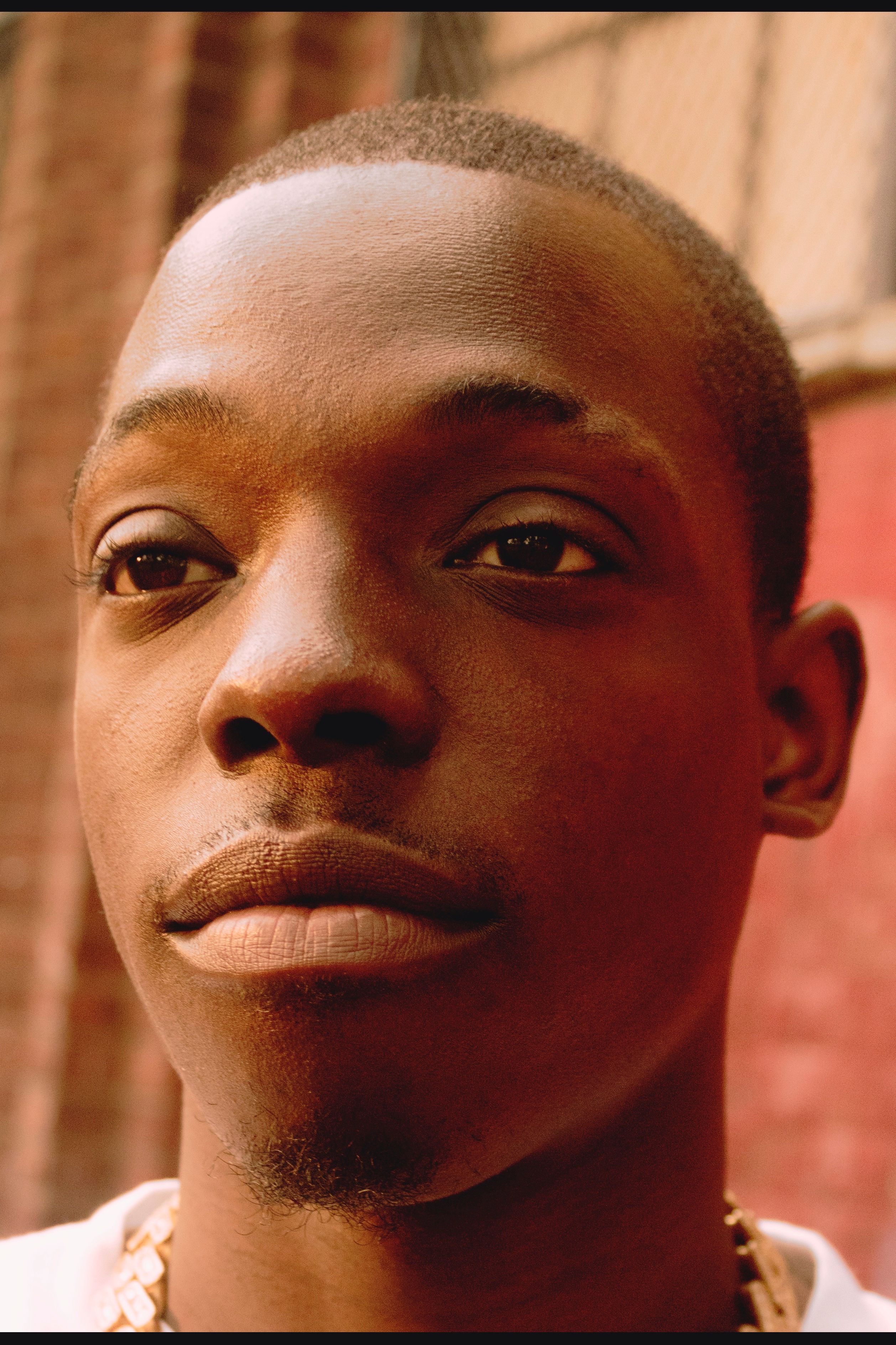

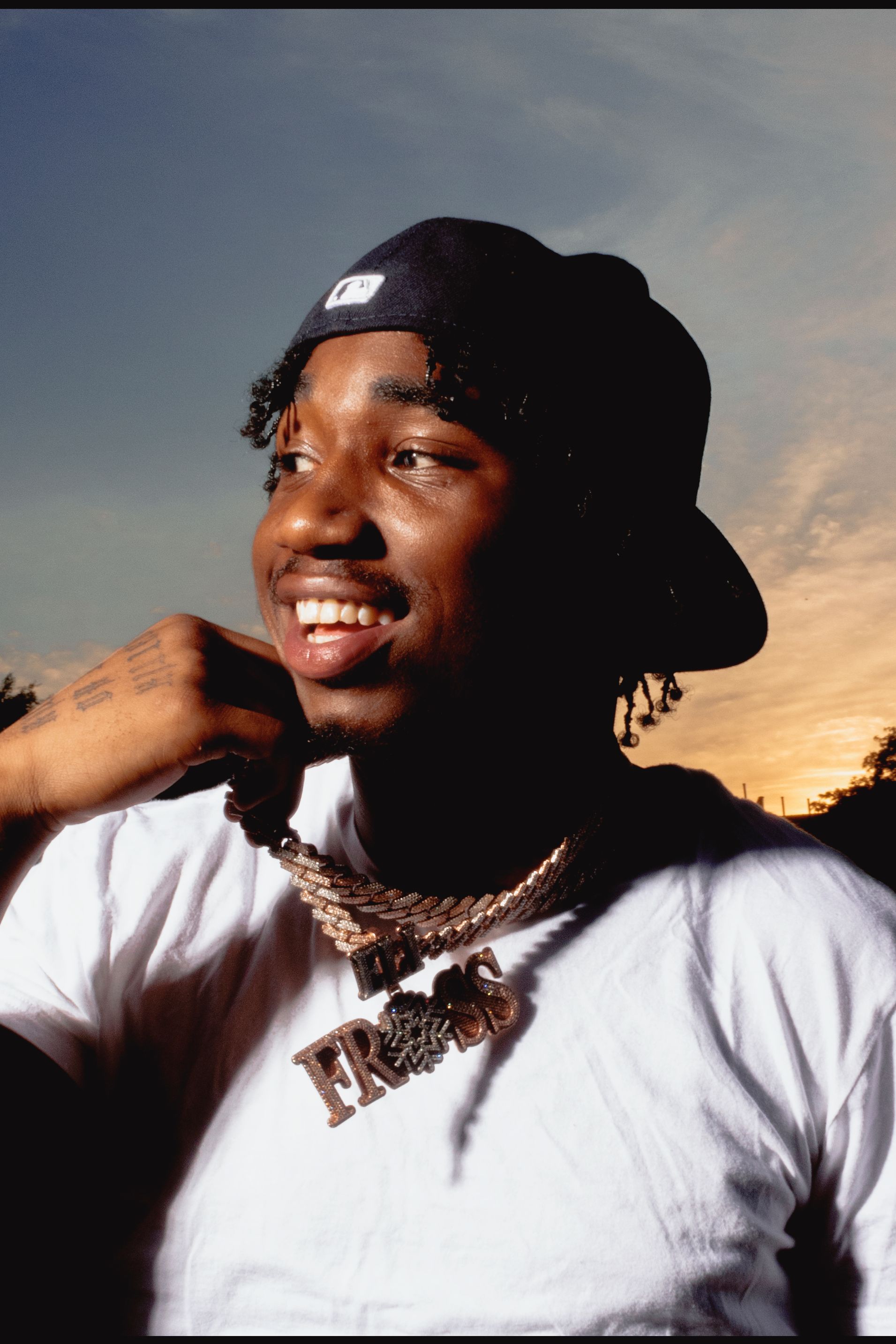

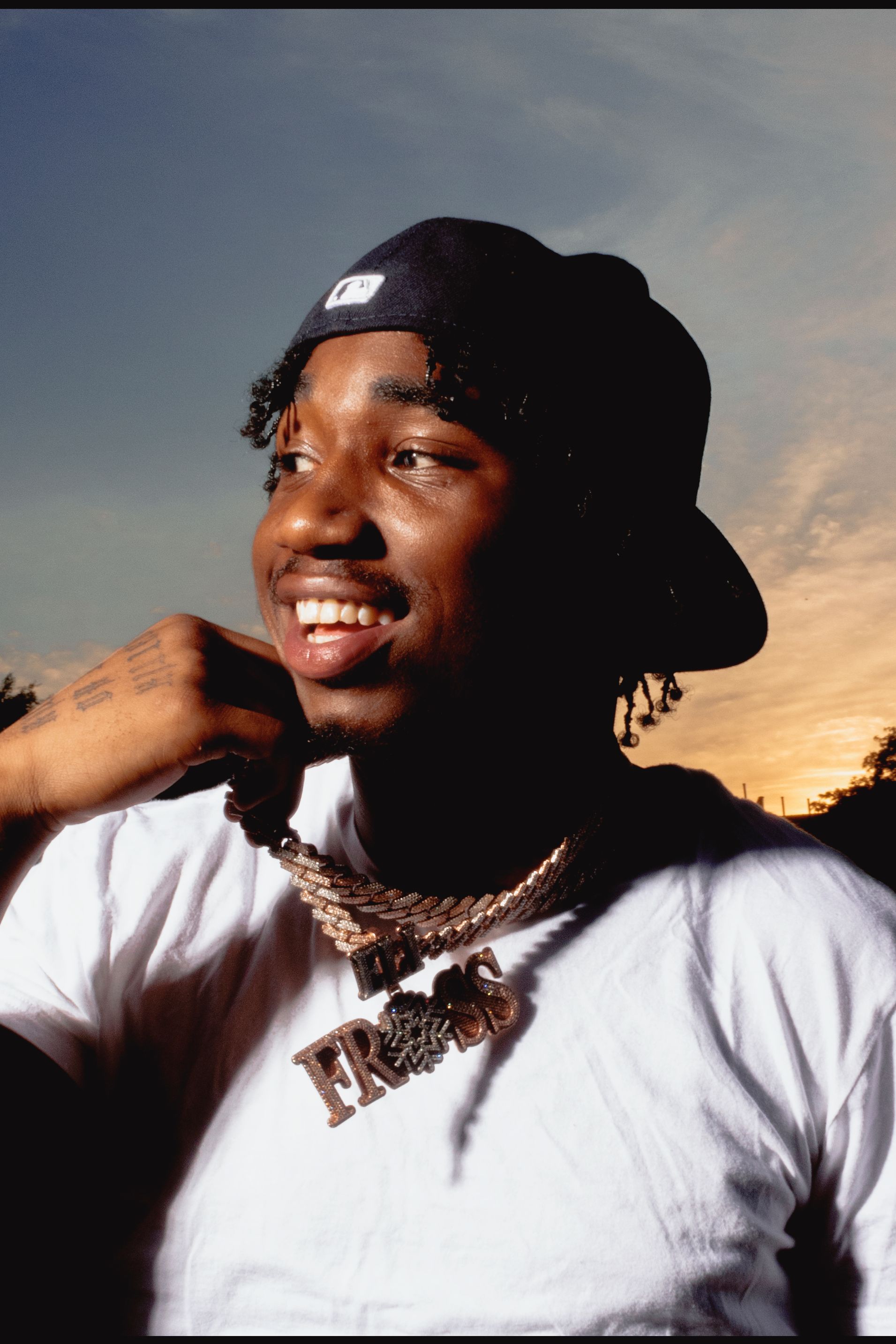

➼ Twenty-one-year-old Dougie B (pictured), 21-year-old B-Lovee, and 19-year-old Kay Flock are childhood friends who became three of the newest faces of Bronx drill after their first hit, “Brotherly Love,” gained attention in 2021. In December of that year, Flock was arrested on murder charges. (He could not be reached for an interview.) Still, his career continues to ascend. In April, Flock and Dougie released “Shake It,” featuring Cardi B.

21, The Bronx

Me, Kay Flock, and B-Lovee — it’s deeper than just friendship. Those are my brothers. We all grew up with each other, going on ten years. That we all made it and could bring along groups of people we know, it’s a great feeling.

21, South Bronx

During the pandemic, we didn’t really have much to do, but we had a studio in the projects. We were just in there making music for fun until we gained a fan base. They encouraged us to take it seriously. It’s a life-changing thing. I just want for artists to be smart. We need to deal with the criticism and just face the fact that there’s gonna be stuff to overcome.

26, East New York

➼ Rah Swish started rapping in 2015 at the encouragement of friends and had a local hit, “Debo,” in 2017. He signed to Woo Entertainment/Empire in 2020 and has since put out two albums.

You could listen to Jay-Z or Nas back in the day — they were talking about drugs, gangs, guns. That’s true of almost every genre of music that got something to do with hip-hop. As drill continues to grow mainstream and street rappers make money off it, then you will have more drill music that’s got to do with lavish living. You not going to be rich and go on shopping sprees and take vacations and still be talking about the same thing. Right now, drill is still in a baby form.

22, Co-Op City

➼ Bronx native Ron Suno started rapping when he was 13. He released his debut album, Swag Like Mike, in 2020 and dedicated it to those who inspired him: Michael Jordan, Michael Jackson, and Mike Tyson.

I want to be the Michael Jackson of drill. Bronx drill is oriented toward dancing. It’s connecting more with the kids on TikTok. When we filmed the video for my song “Grabba,” we shot it at the train station and in the middle of the street. We had the kids outside. There were homeless people dancing. It felt like the cops were liking it, too. They were just telling us to stay safe. We were all having fun.

23, Canarsie

➼ Dusty Locane was a childhood friend of the late Pop Smoke, the prodigy who put New York drill on the map in 2019. For many, 20-year-old Pop Smoke was elevated to legend status after his shooting death in February 2020 during a botched robbery in Los Angeles. Locane has often been compared to the artist for their similar voices and styles.

I was born and raised in Canarsie. From my hood, the only other person to do it was Pop. I don’t talk about it much, but I grew up with him. I’m talking about sleepovers-in-my-crib type shit. He let people from where we’re from know that it’s possible to make it. I’ll always be grateful to him for that because outside of him, unless you’re talking about Biggie, there’s not that many people with that bass, that deep voice that know how to home in on it. Pop did that too. He opened that door.

I try not to get into politics too much when it comes to what the mayor is saying about drill. I just know I understand what drill really is; it’s an art where we get to let our emotions out without actually murdering, robbing, or breaking into somebody’s home. A lot of people will look at us and say we’re vulgar, we’re disrespectful, we’re violent. We get pulled over three, four times a day, and all they want to know is if I got guns in the car.

The odds are always going to be against us. Whether it’s the cops, whether it’s the opps, whether it’s somebody you don’t know from a hole in the wall that’s just jealous. You got to just be very, very, very eyes open. It’s not a good way to live.

That’s why I get the younger crowd. Everything for them is flashing a gun, but I try to tell them, “Yo, if you want to flash your gun, put it in a story line.” Because now you not just waving guns in the camera; you’re showing me a piece of your life through the music.

I wish Pop could have still been here because I feel like he would have put us back on top faster. You see how down South you got that sound we all know: DaBaby, Young Thug, all them. We would’ve been another example of it. But we’re still building. The East is still holding it down.

➼ Twenty-one-year-old Dougie B (pictured), 21-year-old B-Lovee, and 19-year-old Kay Flock are childhood friends who became three of the newest faces of Bronx drill after their first hit, “Brotherly Love,” gained attention in 2021. In December of that year, Flock was arrested on murder charges. (He could not be reached for an interview.) Still, his career continues to ascend. In April, Flock and Dougie released “Shake It,” featuring Cardi B.

21, The Bronx

Me, Kay Flock, and B-Lovee — it’s deeper than just friendship. Those are my brothers. We all grew up with each other, going on ten years. That we all made it and could bring along groups of people we know, it’s a great feeling.

21, South Bronx

During the pandemic, we didn’t really have much to do, but we had a studio in the projects. We were just in there making music for fun until we gained a fan base. They encouraged us to take it seriously. It’s a life-changing thing. I just want for artists to be smart. We need to deal with the criticism and just face the fact that there’s gonna be stuff to overcome.

26, East New York

➼ Rah Swish started rapping in 2015 at the encouragement of friends and had a local hit, “Debo,” in 2017. He signed to Woo Entertainment/Empire in 2020 and has since put out two albums.

You could listen to Jay-Z or Nas back in the day — they were talking about drugs, gangs, guns. That’s true of almost every genre of music that got something to do with hip-hop. As drill continues to grow mainstream and street rappers make money off it, then you will have more drill music that’s got to do with lavish living. You not going to be rich and go on shopping sprees and take vacations and still be talking about the same thing. Right now, drill is still in a baby form.

22, Co-Op City

➼ Bronx native Ron Suno started rapping when he was 13. He released his debut album, Swag Like Mike, in 2020 and dedicated it to those who inspired him: Michael Jordan, Michael Jackson, and Mike Tyson.

I want to be the Michael Jackson of drill. Bronx drill is oriented toward dancing. It’s connecting more with the kids on TikTok. When we filmed the video for my song “Grabba,” we shot it at the train station and in the middle of the street. We had the kids outside. There were homeless people dancing. It felt like the cops were liking it, too. They were just telling us to stay safe. We were all having fun.

23, Canarsie

➼ Dusty Locane was a childhood friend of the late Pop Smoke, the prodigy who put New York drill on the map in 2019. For many, 20-year-old Pop Smoke was elevated to legend status after his shooting death in February 2020 during a botched robbery in Los Angeles. Locane has often been compared to the artist for their similar voices and styles.

I was born and raised in Canarsie. From my hood, the only other person to do it was Pop. I don’t talk about it much, but I grew up with him. I’m talking about sleepovers-in-my-crib type shit. He let people from where we’re from know that it’s possible to make it. I’ll always be grateful to him for that because outside of him, unless you’re talking about Biggie, there’s not that many people with that bass, that deep voice that know how to home in on it. Pop did that too. He opened that door.

I try not to get into politics too much when it comes to what the mayor is saying about drill. I just know I understand what drill really is; it’s an art where we get to let our emotions out without actually murdering, robbing, or breaking into somebody’s home. A lot of people will look at us and say we’re vulgar, we’re disrespectful, we’re violent. We get pulled over three, four times a day, and all they want to know is if I got guns in the car.

The odds are always going to be against us. Whether it’s the cops, whether it’s the opps, whether it’s somebody you don’t know from a hole in the wall that’s just jealous. You got to just be very, very, very eyes open. It’s not a good way to live.

That’s why I get the younger crowd. Everything for them is flashing a gun, but I try to tell them, “Yo, if you want to flash your gun, put it in a story line.” Because now you not just waving guns in the camera; you’re showing me a piece of your life through the music.

I wish Pop could have still been here because I feel like he would have put us back on top faster. You see how down South you got that sound we all know: DaBaby, Young Thug, all them. We would’ve been another example of it. But we’re still building. The East is still holding it down.

.

Listen to 19 of the artists who define NY drill

More on drill music

- Everything We Know About Sheff G and Sleepy Hallow’s Indictment

- A$AP Rocky Takes ‘Full Responsibility’ for Short Rolling Loud Set

- The Drill Songs to Know

- What Happens When Drill and the Justice System Clash in the Courtroom?