This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

In 2009, when the comedian Nathan Fielder first moved to L.A., he learned to tell his managers not to send him to meetings. Why bother? If the point was to charm people into giving him a job, sitting down with them could only hurt his chances. “I’d always say, ‘If people like the stuff I’m making, I’m not going to do anything to heighten that in person,’ ” he recalled. “I’m not going to be very funny in the room.”

This was not necessarily a case of false modesty. Fielder did not initially strike all of his friends and colleagues as the most engaging personality. Tim Heidecker, who met him in 2010, was bewildered when he heard Fielder was pitching his own show, Nathan for You, to Comedy Central. “Who? That guy?” the comedian remembered thinking. “He’s deceptive,” said Jimmy Kimmel, who has had Fielder on his show several times. “Because you look at him and you go, Oh, this seems like a normal guy. Maybe even a boring normal guy. Maybe even a guy I’d be bummed I had to sit next to on a plane.”

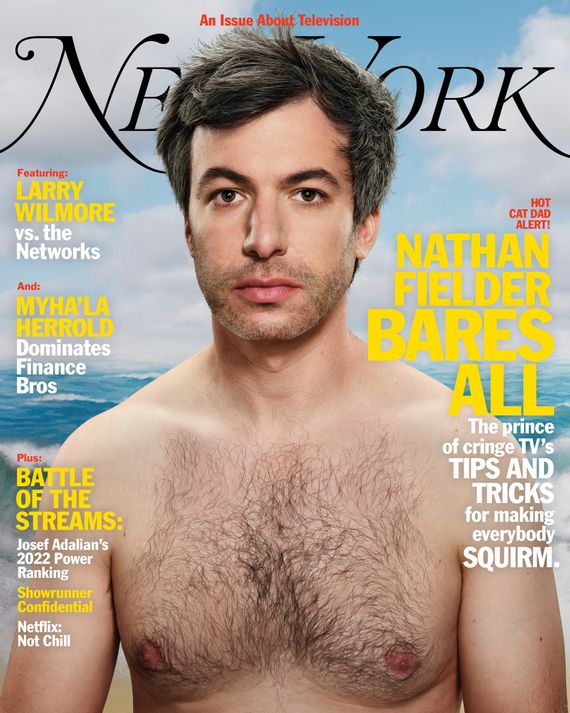

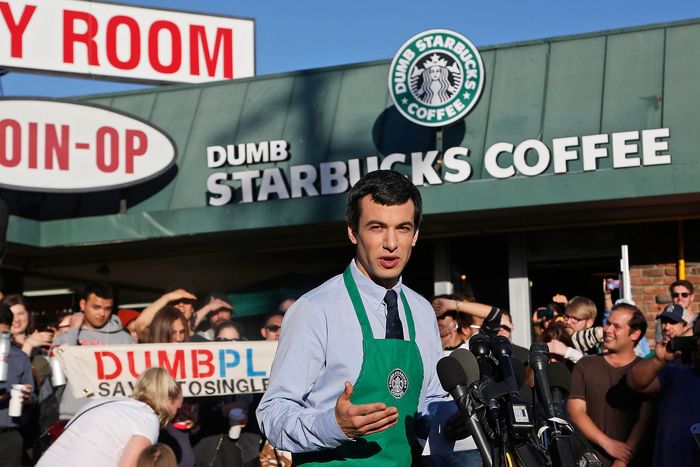

On Nathan for You, Fielder used his façade of bland charmlessness to get people to do and say astonishing things. The cult hit, which ran on Comedy Central from 2013 to 2017, was a kind of parody of business-improvement shows like Kitchen Nightmares. In a typical segment, Fielder would visit a real small business, usually somewhere in the Greater Los Angeles area, and pitch the owner on an absurd idea — poo-flavored frozen yogurt, a special soundproof box in which vacationing parents could confine their children while having sex in a hotel room. His manner, an unusual combination of gentle and pushy, arrogant and insecure, suggested both a desperate desire to be liked and a pathological inability to understand why he wasn’t. He asked intrusive questions, stood too close to people, and leaned in even closer when they tried to pull away. What made the show outrageously funny, and arguably kind of mean, was his relentless commitment to the role. Even as his subjects squirmed in discomfort, he delivered his pitches with such conviction that people nearly always agreed to try whatever scheme he proposed, no matter how ridiculous it made them both look.

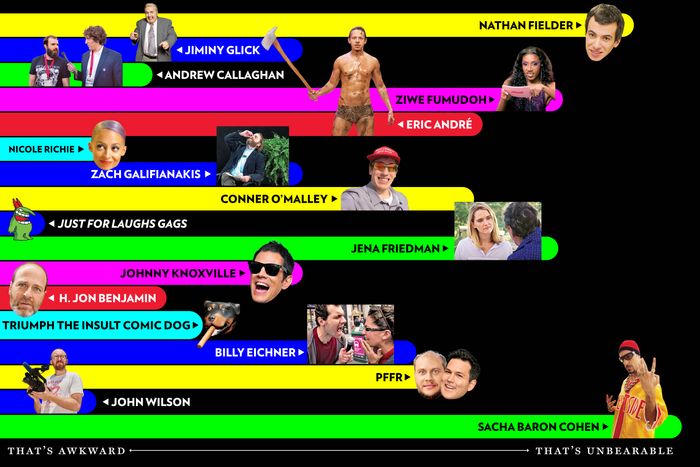

The show positioned Fielder, now 39, at the forefront of what the New York Times recently hailed as a “quiet revolution” in comedy. Along with Sacha Baron Cohen and John Wilson, both of whom have collaborated with him, he belongs to a contingent of comedians who specialize in exposing the sorts of behavioral quirks, the unsightly warts of the self, that we are forever trying to hide. In an age of fake news and filtered pics and Big Lies, his genre — some call it “reality comedy” — has become an improbable source of precious truth. Unlike, say, Baron Cohen, scourge of NRA shills and Rudy Giuliani, Fielder isn’t especially interested in politics. What distinguishes him, along with the diabolical intricacy of his pranks, is the depth of his interest in the human psyche. “I occasionally was able to draw out some things the interviewee wouldn’t normally reveal on a television show, but he’s able to draw out more,” said Baron Cohen, one of the pioneers of the form. “He took the genre I stumbled into and moved it forward.” He’s about to move it even further. The Rehearsal, on HBO, marks Fielder’s return to acting and directing for the first time in five years, and it is his most ambitious, thrilling, and personal work yet.

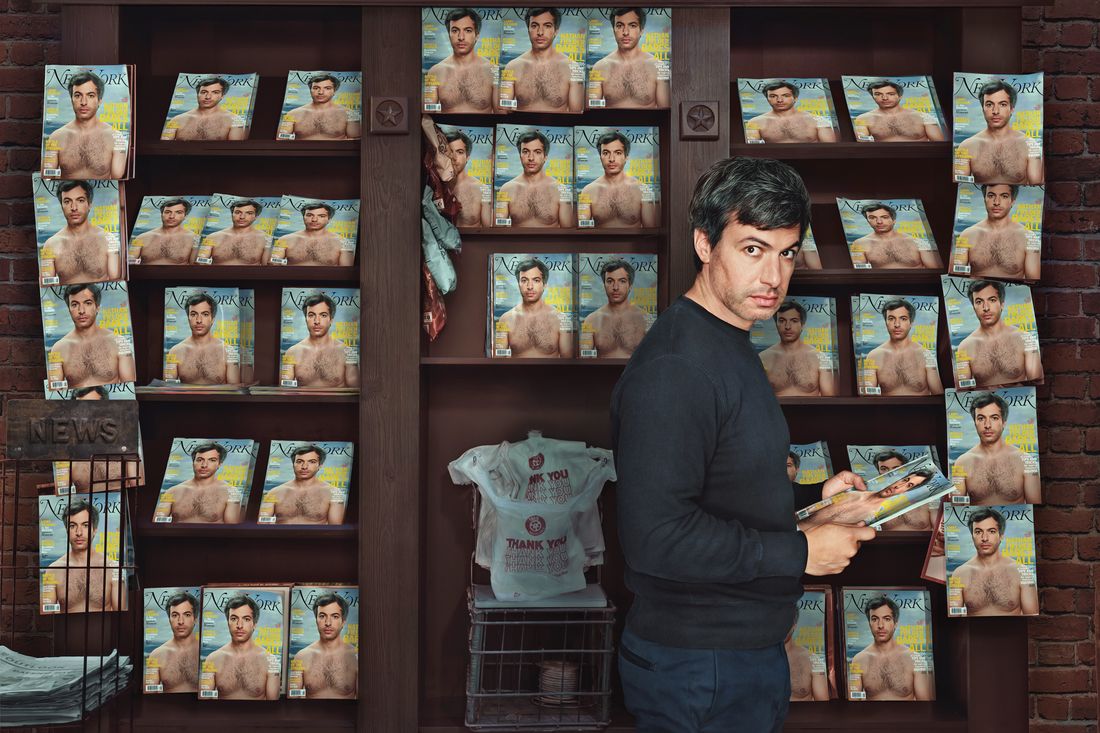

Nathan for You was set in an L.A. devoid of Hollywood glamour or Silver Lake chic, a world of electronics chains and mall Santas and business-casual khakis. Fielder lives in Silver Lake, but he seems to belong to that world, too. When I met him at his door, he was dressed in a nondescript outfit of black chinos, white T-shirt, and gray New Balances. In his living room, there was a beige couch, some fluffy white pillows — the kind of neutral décor you might find at a perfectly nice Airbnb. There are multiple streams of internet discourse devoted to identifying the source of his inexplicable attractiveness. Perhaps it’s not so inexplicable. Out in the world, he is witty, self-deprecating, and successful. He has a slim build, a still-boyish face, and the thick, slightly unruly salt-and-pepper hair of a grad student who just spent a month in the lab pulling consecutive all-nighters. Fielder speaks in the same flat, stilted voice he uses on the show, but in person, it’s infused with a tone of perpetual, bone-dry amusement. Heidecker, who eventually came to appreciate his subtle charms, described him as the consummate straight man. “He’s a really fun person to be an idiot around,” he said. “I might say, ‘We should start eating dog food,’ and he’d be like, ‘Why would I do that?’ ”

At his house, Fielder introduced me to his cats, Jackie and Rocket, who trailed us into the kitchen and jumped onto the table. “When I got them, they were kittens,” he said. “There were like ten brothers and sisters grouped together, all cuddling, and then one off to the side.” Jackie was the outcast. “I was like, I want her,” Fielder said. “She maybe has some behavioral issues,” he added uncertainly. A cat, of course, is a creature that doesn’t cooperate with anyone’s agenda but its own. Fielder can be the same way. Before I had a chance to ask my first question, he had asked me several: Did I get my reporter’s notebook on Amazon? Wasn’t it a shame that when I opened it to take notes, my interview subjects couldn’t see the word NEWS printed in large block letters on the cover? We sat at the kitchen table, and I finally asked how he was doing. “Well, I hate talking about myself,” he said. He claimed this had something to do with a lifelong struggle to articulate his thoughts. When he was in elementary school, a speech therapist told him he knew fewer than 500 words, which bothered him so much his mother gave him a book of advanced words like abreast. (“Not ‘a breast,’ ” he clarified.) “I still, to this day, feel like I don’t know a lot of words. Maybe it’s that.” He shook his head. “I don’t know.”

He hopped up from the table and began pacing around the kitchen island, searching for a pair of claw clippers. “Did he claw you?” he asked, looking at Rocket, who had planted himself on top of my recorder and had not clawed me. He saw me writing something in my notebook. “Are you writing ‘Cat clawing Nathan’?” He laughed. “ ‘Cat does not like Nathan,’ ” he continued. “ ‘Nathan’s own cat does not like him.’ ” As we left the house, he asked if I would ever abandon a story after it had been assigned. “What would I have to do to make you bail?”

The Rehearsal, like all of Fielder’s work, is not quite what it seems at first. The show’s sparse marketing materials describe it as a series about “the lengths one man will go to reduce the uncertainties of everyday life.” In the opening scene of episode one, Fielder walks into the apartment of a middle-aged teacher who has responded to a vague Craigslist ad. In a video submission, the teacher has confessed to Fielder that he has spent years agonizing over a lie he told a friend on his trivia team about his educational background. The Fielder who greets him isn’t exactly like the one we have seen before. He is warmer, more inclined to smile. In the voice-over, he notes he’s been told his personality can make people uncomfortable, so he tries a few jokes. He notices a lot of doors in the apartment. “Door city over here!” he exclaims with a shy grin. The teacher laughs awkwardly.

Fielder has come to this apartment to offer what may sound like an extraordinary gift. Enlisting a construction crew and a small army of actors, Fielder will build a set and direct a series of rehearsals that will allow the teacher to practice confessing his secret to his friend, over and over. What if, the show asks, we could know what will happen in our lives before it happens, could prepare for every way it might unfold? What if we could take control of our futures? There is something poignant, and kind of wonderful, about what Fielder appears to be proposing, but anyone who’s watched Nathan for You knows his objective is never straightforward. “There’s a real Milgram quality to Nathan,” said the actor and comedian H. Jon Benjamin, referring to Stanley Milgram, the eccentric and visionary psychologist known for a notorious study of obedience, begun in 1961, in which he lured subjects into administering what they believed were electric shocks to other participants. “It always seemed like he was from another planet learning how to do human customs,” Benjamin told me, “or AI collecting information on human behavior.”

At his cluttered office in a rental house in Echo Park, Fielder flipped open his laptop and zoomed into the writers’ room for How To With John Wilson, an HBO show for which he serves as an executive producer. Fielder met Wilson by chance in January 2018 at a restaurant in New York with a group of mutual friends. He had recently wrapped the final season of Nathan for You and was trying to figure out what to do next. Fielder says Comedy Central wanted more seasons of the show, but he was ready to move on. He happened to see one of Wilson’s documentary shorts about his experience as a plaintiff on a court TV show, where he had appeared after deliberately filing a bogus lawsuit. That night at dinner, Fielder suggested they make a show together. “He wanted to pour his energy into something,” Wilson told me. “And he completely changed my life.”

If Fielder is like Milgram, designing experiments to study how people behave, Wilson is more of an anthropologist, obsessively observing humans in their natural environments. He strolls around New York with a camera, recording interviews with New Yorkers and surreptitiously documenting their strange customs (a woman placing a pigeon into a shopping bag, a man dragging an air conditioner down the street on a leash). The episodes take inspiration from the most basic genre of internet content: the instructional video. Each tackles a different topic: how to make risotto, how to throw out batteries, how to make small talk. But Wilson is not actually interested in teaching anyone how to make risotto. He’s interested in exploring his struggles with making risotto — and with discarding batteries and chatting with people at parties and all the other confounding aspects of existence that seem to make the life of John Wilson a perilous adventure. Fielder’s role in the writers’ room is to broaden the scope of these investigations, to lead Wilson down alleys of inquiry he might not have otherwise thought to pursue.

Today, they were trying to hammer together a provisional script for an episode of the show’s third season. The topic filled Wilson’s heart with trepidation. “Is there anything new,” Fielder asked, “on the public-bathroom front?” Wilson and the two other writers in the room — Michael Koman, an EP on How To and the co-creator of Nathan for You, and Allie Viti, a How To associate producer — stared back at him. They had already spent days talking about how hard it can be to find and use a public toilet, analyzing the problem from every angle, but they were still struggling to answer a basic question: Why does this mundane fixture of modern life make people so anxious? “It’s all relative to the sound other people make,” Fielder proposed. “If other people are farting a lot, you’ll never feel self-conscious.”

Koman disagreed: “I think all it takes is a pair of shoes to just completely seize up.”

Wilson, peering through thick glasses, nodded. “I feel like some people might wear different shoes in the bathroom just so that when you look under, you don’t know it’s them.”

Fielder clasped his hands together professorially. “Obviously, it’s terrifying to make any noise in a bathroom with other people,” he conceded. “One strategy, if you had to make a sound with your bum, is to spread your cheeks wider to avoid the fart noise.”

At Fielder’s prompting, they considered the amazing variety of public toilets throughout the city. Koman reflected on the comfort and “dignity” he felt upon taking a dump in Japan, where the toilet seats are sometimes heated, which got Fielder thinking about whether there are people who, because of what they do for a living, don’t care if a bathroom is clean and comfortable. Fielder proposed sending Wilson to a morgue to interview its employees about the “bathroom politics” of the place. If even people who are comfortable with corpses feel anxious about using public toilets, that would be a “ ‘no hope’ moment” for the rest of us, Fielder said.

The challenge would be getting those people to respond honestly. Fielder understands that when people go on reality TV, they have certain expectations for how they’re supposed to act. In his own shows, he uses a variety of tactics to throw his subjects off-balance — needling or misdirecting them, sitting in excruciating silence until they crack. In one episode of Nathan for You, a Realtor reveals she was once choked by a ghost in Switzerland; in another, a gas-station owner nonchalantly says he drinks his grandson’s pee when he’s scared. As Fielder sees it, uncomfortable situations can prompt people to expose parts of themselves they usually try to conceal — qualities that make them unique and often endearing. On the Zoom, he suggested that Wilson interview the workers without telling them the episode was about bathrooms. If the subjects knew the topic was toilets, they would surely clam up or, worse, try to be funny.

When Fielder was 13, he had a friend whose father and grandfather were both magicians. One day, the friend showed him a simple card trick. Fielder begged him to teach him how to do it. He and the friend joined the Vancouver Magic Circle, the only kids in a sea of old men. He got a job at a magic store in the mall, carried a deck of cards around with him at all times, and started performing at children’s birthday parties. One night at dinner, he agreed to show me the feat of deception that short-circuited his brain all those years ago. “It’s not that impressive,” he warned, slipping a worn business card from his wallet. “See the card?” With a flick of his wrist, the card disappeared. I asked him to do it again. Fielder smiled. “No, I’m not going to do it again.”

Our table was illuminated by the ambient glow of an enormous sign affixed to an IT’SUGAR across the street. We were at a Japanese restaurant in an outdoor mall at the Universal Studios theme park, a sprawling monument to crass consumerism, seductive storytelling, and the allure of animatronic dinosaurs. I asked Fielder what drew him to magic as a kid. His hesitation to answer this sort of question did not come as a surprise. Fielder’s colleagues have described him as a genius in the edit room, a master at pulling narratives out of countless hours of incoherent footage, but he’s less confident when it comes to telling his own story. I had already heard the following speech several times with slight variations: “I think you can build a story for yourself and retroactively say, ‘Well, that probably was this.’ You’re looking for the logical connections. It’s nice to tell a story that way, but I don’t know if that’s always what’s happening.” He fiddled with his chopsticks, rolling them in his fingers. “I don’t know. Maybe.”

Fielder grew up in Vancouver, the child of two social workers, civil servants who helped people injured on the job. The family had no cable, only a handful of VHS tapes his grandfather had recorded, including a Peter Pan musical that still aired on public television in the ’80s. On Halloween, Fielder’s parents would take away his candy and replace it with healthier snacks. They sent him to a Jewish elementary school that he remembers mostly for its emphasis on Holocaust education. “They were showing us dead bodies at a very young age,” he said. At 13, he transferred to a large public school, a bewildering experience. “I didn’t understand how people made friends,” he said. Performing magic, he soon discovered, was easier than conjuring small talk. “You’re saying, ‘Here’s what we’re going to engage about.’ And then when the trick is done, the interaction ends,” he said with a laugh. Around that time, he joined the high-school improv team. One of his partners, who happened to be Seth Rogen, recalled how Nathan was always doing his own thing during warmup exercises. “It was not even on the table that he would act like he was burning in lava,” he said.

After studying business at the University of Victoria, Fielder got a job, briefly, at a brokerage, which he found depressing. He decided to give himself a year to see if he could succeed as a comedian, so in 2005 he moved to Toronto for Humber College’s comedy program and joined a collective called Laugh Sabbath. He bought a video camera and made hundreds of experimental shorts. Katie Crown, a frequent collaborator, recalled that Fielder had a particular idea of fun. Sometimes he would dare her to do something absurd, like draw a goatee on her face in chocolate sauce, then turn to a waiter and pretend everything was normal. When he presented his videos at the Laugh Sabbath weekly show, he noticed that people often laughed at aspects of the work he hadn’t intended to be funny — his voice, his facial expressions. It felt freeing. “There was a transition where I went from trying to hide the embarrassing parts to appreciating the things about myself that I hated before,” he said.

Fielder’s videos caught the eye of a producer on This Hour Has 22 Minutes, Canada’s equivalent of The Daily Show. In 2007, he developed an interview segment for the show called “Nathan on Your Side.” He went around the country in a shirt and tie confronting real people with questions no local correspondent would ever ask. In one, he sits down with a professional matchmaker and inquires when they will “get to the kiss.” Is this a hypothetical question, or does he really expect her to kiss him? All the essential elements of the Nathan for You persona are already in place — the inscrutable affect, the disturbing man-child’s gaze, the talent for responding to an awkward moment by making it ten times worse. “Whenever both people are feeling like they’re ready,” the matchmaker replies, looking a little concerned about where this is headed. “Okay,” he presses on. “Are you feeling like you’re ready?” She tries to break the tension with a joke. “Sure,” she says, laughing, “We just won’t tell my husband.” “Okay,” he replies. The camera lingers on her panicked expression as her laughter slowly grows brittle and dies. By the end of the segment, he is holding his face inches from hers.

When Fielder was in his mid-20s, Koman, then working as the head writer of the Comedy Central sketch show Important Things With Demetri Martin, hired him as a writer. One of his colleagues on the show, H. Jon Benjamin, found him to be endearing, and odd. “We’d go out to eat, and everyone would order, and then the waiter would come to him and he would stall,” he recalled. “He would ask about every dish. He would ask what the ingredients were. I remember him asking about chicken teriyaki for, like, three minutes — ‘What’s in it? What’s in the sauce? Do you like it?’ — to the point where the server was like, ‘I don’t have time for this.’ The assumption, I think, was that it was a joke, and it was the most entertaining thing to watch. But he was not joking — he could not order. It was like he’d spent six years alone in his room doing magic and was now wandering around like a foreigner in this world.” Benjamin offered Fielder a job acting and writing on his Comedy Central series Jon Benjamin Has a Van. During Fielder’s tenure on the show, he and Koman pitched Nathan for You to Comedy Central. When Benjamin first watched it, he was struck by how much of Fielder he saw in the work. “He was kind of exposing his own obsessive personality disorder,” he said.

It was 2011, an ideal time for Fielder to sell a show as strange as Nathan for You to a television network. Jackass and Baron Cohen had proved that America had an appetite for absurdist stunts, and The Office had revealed our desire for scenes of excruciating awkwardness set in the drab confines of a suburban business environment. But Fielder’s interests had always been more obscure. One of the artists he admires is the British mentalist and illusionist Derren Brown. In one of Brown’s television specials, which Fielder suggested I watch, Brown brainwashes businesspeople who have never been in trouble with the law into committing what they believe to be a genuine armed robbery. “He’s a guy who made something where you can’t figure out how it’s done and how it’s so good,” Koman said. “If I had to guess what drove Nathan, it would be to feel like he made something that had those qualities.”

In its best moments, Nathan for You didn’t just make you laugh. It provoked feelings of awe, affection, and, not infrequently, a desire for a vortex to open up in the center of your couch and swallow you whole. In the 2015 season-three finale, which deviates from the show’s business theme, Fielder sets out to help Corey, a “hopeless” man with a dead-end job, get a girlfriend and become a “national hero.” In a typical reality show, this would have involved a fitness program, a makeover, a session or two with a lifestyle guru. Fielder, instead, yanks back the curtain on the American obsession with personal transformation, the belief in the quick fix, the overnight success, that stretches back to Dale Carnegie and beyond, revealing the emptiness at its core.

The episode took more than six months to make. Fielder begins his quest by hiring a fourth-generation circus performer to teach him how to walk on a wire. Then he disposes of Corey, hiding him for two weeks in a trailer in the Mojave Desert. With the ostensible protagonist safely out of the way, Fielder puts on a padded bodysuit and a prosthetic mask of Corey’s face and becomes him. He meets a woman named Jasmine while posing as Corey online, goes on a date with her, and spends the whole night dancing. “It was nice, for once, to have a night away from all my insecurities,” he drones in a voice-over.

In reality, this performance was a grueling test of stamina. Eric Notarnicola, a writer and editor on the show, recalled Fielder sitting in the makeup chair for some four hours each day for two weeks while technicians painstakingly affixed the Corey prosthetic to his face. “It would look like he was crying, but it was just sweat that was pouring out of the holes between his eyes and the mask,” Notarnicola said. “He’d torture himself to get a good scene.”

The climax of the episode is one of the most troubling, profound, and funny sequences in all four seasons. Wearing Corey’s face, Fielder walks back and forth across a wire strung between two seven-story office buildings while a crowd of spectators, reporters, and Corey’s grandparents cheer him on. At last, hidden from the crowd in a tent on the roof, he switches places with Corey, instructing him to walk out into the waiting arms of Jasmine, a woman he has never met. Corey tells Fielder he’s confused by what’s happening, but once he leaves the tent and hears the roar of the crowd and sees the girl beaming at him, he meets the moment. Following Fielder’s directions, he asks if she wants to kiss. She consents, if you can call it that given all the false information she’s been fed. Corey looks out at the crowd and the news cameras below and delivers a speech Fielder wrote for him, glowing with unearned pride. Corey’s response to Fielder’s scheme, and the crowd’s response to Corey, captures so much of what Nathan for You reveals about human nature — our willingness to do what we’re told no matter how wrong it seems, our credulous belief in heroes and tidy narratives. As the episode winds down, the camera dwells on a close-up of the lonely magician, the sad clown behind it all. Makeup artists peel away the prosthetic face, revealing Fielder’s dead eyes, his empty expression, like something from a horror movie about the death of the American Dream.

Fielder said his mother thinks of what he does as ethnomethodology, an obscure discipline of sociocultural analysis. Ethnomethodologists attempt to examine society through the study of ordinary people and everyday affairs, in part by designing experiments aimed at disrupting the rules that govern human behavior. In one classic experiment, the discipline’s founder, Harold Garfinkel, instructed his students to pretend to be lodgers in their own homes without revealing to their parents and siblings what they were doing. “For the most part, family members were not amused,” Garfinkel later noted in his 1967 book Studies in Ethnomethodology, the defining text of the field. Even after the students explained their assignments, the unwilling subjects felt manipulated and used. “Please, no more of these experiments,” the sister of one student begged. “We’re not rats, you know.”

When Nathan for You first aired, many critics hailed it as brilliant, but some wondered if it wasn’t also cruel. On a Slate culture podcast in 2014, Dan Kois said there were moments when “the concepts really hit” and other times that made him “deeply unhappy” with himself “and the world.” Watching the show, it was sometimes hard not to worry for the people who were in it. Did they know what they were getting into?

The answer is not usually, at least not at first. Fielder’s producers would typically tell business owners he was making a show about small businesses for MTV Networks (Comedy Central’s parent company). Fielder tended to appear after the contracts were signed and the cameras were rolling. Some realized the joke early on and were happy to play along. Joy Lazarus, then the owner of a ranch that offered horseback rides, didn’t mind Fielder’s tendency to ask so many unusual questions. “He was really intrigued by the horses,” she said fondly. The widow of the late Judge Filosa, a recurring character, said Fielder and his crew showed up to his funeral. “That show was the best thing that could have happened to him,” she said. “He loved it.”

Others were upset by the experience. In season three, Eric Belland was working as the manager of an outdoor-clothing store where Fielder set up a display for a windbreaker he’d designed to raise awareness of the Holocaust. Belland was offended by the display itself — “bodies in ovens at the service of humor” — and felt Fielder had cast him as the “rube.” He didn’t feel any better when he saw the episode and realized it was all a joke. “He looks like an idiot within the confines of the show,” he said, “but he looks like a nasty trickster outside the confines of what the show is supposed to be.” Mark Rappaport, the inventor of a toy called the Doinkit, said he knew Fielder was doing a bit after just a couple of minutes with him but disliked him anyway. “He was trying to get me to say things that would be harmful to my business,” he said, “and to show how funny he was.”

It can be hard to tell just by watching the show how a given subject will feel about it. When fans debate its cringiest moments on Reddit, they sometimes cite a scene with an actress named Victoria Lynn. In that episode, Fielder stages a play at a bar in a highly impractical attempt to circumvent California’s ban on indoor smoking. Lynn was cast in one of the roles. At one point, Fielder proposes an acting exercise. He gazes into her eyes and instructs her to say “I love you.” One of the running jokes of the series is that Fielder is desperate to connect with someone, anyone, and will use his power as a television host to wheedle affirmation out of everyone he meets. “I’m not believing that at this point,” Fielder says in the episode. “Say it again.” She does. “Again,” he says. This happens 11 times, ending only when Lynn points out Fielder has tears in his eyes. Viewers have wondered whether she felt harassed or threatened, but as it turns out, she had a great experience. “He just seemed like he needed to hear ‘I love you,’ ” she told me, “and I felt really comfortable giving him that.”

Fans have often said Nathan for You exposes the cruelty of capitalism, depicting America as a place where people will do nearly anything to survive. But that is also a large part of what can make the show itself unsettling to watch. By focusing on small businesses, it depends on the participation of people who are struggling, many of them immigrants and people of color. In one of the more unpleasant segments, Fielder pitches the owner of the Help Cleaning Service on an idea he says would allow her to offer “the fastest clean in the country.” At his suggestion, the owner dispatches 40 of her employees to a small apartment. Crammed into the place like clowns in a clown car, they manage to clean it in just over eight minutes. After they finish, Fielder lines them up in front of the man who lives there, a middle-aged white guy, and tells them he’s single. When the guy compliments the women on their hard work, Fielder turns to them and jokes, “If you’re lucky, he could do some hard work on you.” The women look unamused.

The owner of the housecleaning service, Kandiie Tapia, is a Mexican immigrant. She was 22 when Fielder’s producers told her they wanted to interview her about how she had built her business. She felt honored that someone wanted to share her story and called her family to tell them the good news. But after the producers rushed her through the process of signing a contract, they “flipped a switch,” she said. During the taping, she found Fielder to be rude. He was in character, but she didn’t know that, or that his technique sometimes involved getting a rise out of a subject. At one point, Tapia said, he blew his nose in a tissue and then asked her if she would throw it out for him. “You’re the Help, right?” she recalled him asking her. (No such exchange made it into the episode.) “It was a power move,” she told me. “Like he’s white and I’m a minority and I’m young.” She talked to her husband about dropping out, but he still thought the show could benefit the business. When the episode aired and Tapia realized it was a comedy, she was so embarrassed she told her family not to watch it. “If I’d known what it really was, I would have said no,” she said. “I’m not gonna go on a show voluntarily to be made fun of.”

Fielder said he was surprised and upset to learn how Tapia felt. “It kills me any time I hear people didn’t like their experience,” he said. “I remember her being very excited about it.” He didn’t recall asking her to throw out a tissue or calling her “the Help” and couldn’t imagine having done that. “I don’t want to invalidate anyone’s experience,” he said, “but I know the types of jokes I might make.” He pointed out that he is the one who is meant to look like a fool in the episode. “I definitely feel I’m the most pathetic person in everything I do.”

Still, he wondered if the core idea of Nathan for You might explain why Tapia would feel upset and he would never know. One of the show’s central jokes is that the business owners think his ideas are dumb but do them anyway. “Sometimes they just want the promotion and they’re making the calculation,” he said. “Sometimes they don’t want to hurt my feelings because they can tell I’m excited about it. And sometimes what might be at play is a power dynamic where the presence of cameras and the pressure of the moment is making them say ‘yes.’ ” When the cameras aren’t rolling, Fielder said, he and his team regularly check in to make sure people want to keep going. His goal “was to give ordinary people an experience outside their day-to-day lives. And generally people have an assumption of reality TV being a fairly absurd thing.” He said only one subject ever quit. But maybe more people hadn’t dropped out because of the very dynamic the show critiques. “You can be checking in with someone and they’re constantly saying, ‘Yes, this is great, let’s do it.’ But it might not be completely true, or later they might change their mind. It’s a weird paradox,” he said. “The thing where we’re satirizing these power dynamics is also a challenge in making the show. And we do get it wrong.”

At Universal Studios, Fielder suggested we take in some culture: a live stunt show based on Waterworld, the 1995 postapocalyptic epic starring Kevin Costner. The movie was a flop of historic proportions, and yet the show, improbably, is still going strong. On a Wednesday afternoon, the stadium was packed and the crowd was shrieking. “What percentage of people here even know Waterworld is a movie?” Fielder wondered.

Life, as Fielder is acutely aware, is unpredictable. The Rehearsal grew out of his exhaustive efforts to anticipate how each episode of Nathan for You would unfold. To prepare for every scene, Fielder and his team had tried to imagine how a reasonable person might react to his unreasonable suggestions, role-playing all the ways an exchange might go down. Even so, people would invariably say and do things Fielder had failed to see coming. After Nathan for You ended, it struck him that it would be interesting to make a show about the futility of trying to predict the future. “It’s sort of universal that people want to have control over their lives,” he said. “There’s something really funny to that compulsion.”

As we waited for the show to begin, a performer hyped up the crowd, blasting a hose directly at a guy in the front row. “We have zero control over where this water goes!” he shouted. Fielder gestured toward a green line a few feet in front of us, the outer boundary of the splash zone. “It’s kind of good because we have a little risk of getting splashed,” he said. With the faintest suggestion of wistfulness, he added that sitting in the splash zone “would be, I guess, the more thrilling experience.” Once the action began, he sat very still, watching closely, his hands tucked beneath his legs. Plumes of smoke billowed out of a seaplane, and a stuntman dove off a 45-foot-high platform while engulfed in flames. “Do you think they dye the water blue to make it look more like water?” Fielder asked. “Looks a little too blue.”

Like the Waterworld show, The Rehearsal involved the construction of an artificial reality. To help the teacher in the pilot episode prepare for his difficult conversation with a friend, Fielder’s team built an exact replica of the Alligator Lounge, the bar in Brooklyn where the two friends planned to meet, down to the rips in the stool cushions. “It was a very expensive pilot,” Fielder said. “One of the crew members told me the cost to replicate that bar was probably more than it cost to build the real bar.” The show’s main story line features a woman who doesn’t know whether she wants to have kids. To simulate the experience of raising a child from birth to 18 years old, Fielder moves her into a house in the countryside and hires dozens of child actors to play her son. From the outset, it’s clear this is an insane idea, but both Fielder and the woman are intent on pretending otherwise, each for their own murky reasons. Despite all the effort that has gone into creating a simulacrum of domestic life, something is off, and the glitches become only more obvious over time. In one scene, the woman dutifully pulls store-bought vegetables out of the dirt behind the house, acting as if she were picking them from a real garden. Later, in the kitchen, as she washes the eggplants, Fielder spots a sticker on a pepper on the counter, then carefully flips the pepper over, concealing the flaw. If Nathan for You showed how easily we could be deceived, The Rehearsal explores our eagerness to deceive ourselves. “I often feel envious of others,” Fielder says in the voice-over. “The way they can just believe.”

As the series progresses, the line between Fielder’s life and work blurs, until he finds himself at the center of his own experiment. At times, he seems to question the wisdom of manipulating people the way he does. When the teacher likens him to Willy Wonka, he looks disturbed. “Isn’t he the bad guy?” he asks. As the credits roll, we hear the eerie tinkling of a celesta, the swell of strings, and then Gene Wilder’s voice, soft as cotton candy. To engineer a moment of intimacy with the teacher, he takes him to a heated pool. Hoping to get the guy to open up, he says he was once married. The teacher begins talking about the pain of his own divorce, but a moment later, the conversation ends. “I didn’t want to go too deep into my private life,” Fielder explains in voice-over, “so I had preplanned for an elderly swimmer to interrupt us.” The Fielder who appears in these scenes is not unlike the real Fielder. “You’re seeing me control and not wanting to share,” he told me. “I’m aware that I’m like that, and so it’s in the show.”

At lunch the day before the Waterworld show, he was reluctant to say much about The Rehearsal. “I don’t want any extra context,” he said. “The thing is the thing.” When I asked if there was anything going on in his personal life that contributed to his desire to make it, he said he wasn’t sure. “You could try to make a story and connect it for yourself, but … I don’t know. It’s hard to know where ideas come from or why you feel something at a certain time.” After a pause, he added, “I did go through a divorce.” He looked down at the table, folding up his paper plate and stuffing it into the little plastic cup.

After relaxing in the splash-free zone, he seemed a little more open to talking about what had happened. He drove me back to my hotel and we lingered in his car in the dark, the engine off but his hands still on the wheel. Fielder had gotten married in 2011 to a children’s librarian he had met at a friend’s comedy show in Halifax. Three years later, in the midst of making the second season of Nathan for You, the marriage fell apart. Everything suddenly felt uncertain. “I was like, Wow, I’m so bad at life,” he said. He wondered whether he could have done something, anything, differently. One day, he broke down in the middle of a big meeting. Losing control of his emotions, he said, was “a very jarring experience.”

He began seeing a therapist just before his marriage ended and discovered it was physically difficult for him to talk about his feelings. “I had a pain in my chest,” he said. “I still get that, but not as much.” He was dating someone now, and they’d recently moved in together. “It’s not always easy to let a person in like that,” he said. “It’s been really nice.” He was silent for a long moment. “I’m, like, really happy.” Saying things out loud to his therapist that he’d never said before had helped. “I’ve shared everything with her,” he said, “and it’s been fine.”

I asked if he had talked about our interview with his therapist. He hesitated. “Ummm … fuck.” His voice dropped to a low murmur. “I wanted to just lie right now.” He began to explain himself: He did not specifically schedule a session with her after speaking with me. He just happened to have one scheduled. “Why am I telling you this shit?” he said, laughing in disbelief. He was growing uncharacteristically animated. “I should have just lied to you just now!” he said. “But I know if I lied in that moment, I would have been caught.”

Would he tell me what he’d told her?

“No!” he said. “No, no, no!”

I pointed out that this is what he does all the time — probe for people’s hidden soft spots. “Of course,” he said, “but you’re going for something different than I might be interested in.” He wanted to get authentic moments out of people, moments you never see on TV. He wasn’t asking them to explain and interpret their lives, to sort their experiences into a narrative, to impart them with meaning. On The Rehearsal, he hires actors to portray real people and then instructs them to follow those people around, engaging them in conversation without ever revealing their intentions. “If the person knows you’re trying to find out about them,” he said, “then they’re not going to present a real version.” Narrative was just another magic trick, an illusion conjured in the edit room.

*An earlier version of this piece misidentified Allie Viti. It has since been updated.